Excerpt: The Cuban Revolution as a Dream of the Diaspora

by Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo / June 2, 2017 / Comments Off on Excerpt: The Cuban Revolution as a Dream of the Diaspora

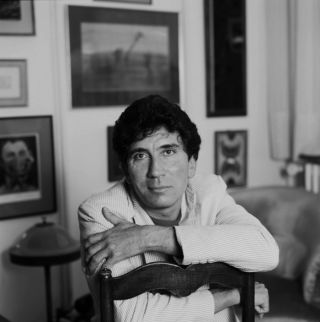

The late exiled Cuban writer, Reinaldo Arenas. Image via The New Yorker.

The Cuban Revolution as a Dream of the Diaspora

Al terminar el sueño, soñaba que estaba en el principio de la noche, en el sitio donde se iniciaba la inscripción de los soplos benévolos. José Lezama Lima1

A childhood dream. Not a nightmare, but a childhood dream. A dream redundantly dreamt by me during my childhood in communist Cuba. Once out of history, now communism is about images taken to the limit. Once out of Cuba, night is my new nation now.

- Is it worth-while to focus on the last images and letters coming from the inside of the last living utopia on Earth? Is Cuba by now a contemporary country or just another old-fashioned delusion in the middle of Nowhere-America? A Cold-War Northtalgia maybe? Can we expect a young Rewwwolution.cu within that Ancien Régime still known as The Revolution? I would like to provoke more questions than answers.

- Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo was born in Havana City and still resides and resists there, working as a free-lance writer, photographer and blogger. He is the author of Boring Home (2009) and is the editor of the independent opinion and literary e-zine Voces.

My childhood. My dreams. My nightmares. My communist country. My Cuba. My vocabulary. My etymology of exceptionalism. My rhetorical rage. My perverse propensity for treasuring possessive pronouns. My amphibological angst. My languishing monolingualism. I, me, mine. And my mother.

It’s 1971. She is singing me a lullaby. The word for lullaby in Spanish is nana. She is singing her only child a nana. Señora Santa Ana: why is your little one crying…? Christian references are floating and fading all over our bedroom. My mother whispers them directly into my newborn brain. Señora Santa Ana: he is crying for an apple he cannot find…

An apple in Cuba! Imaginary Botany in the time of a tyranny called La Revolución. In the succulent seventies of Soviet scarcity. My mother must have resembled the Mother of God. A woman. A first-time mother. Almost a virgin. Challenging with a simple nana the atrocious atheism that Karl Marx’s Caribbean epigones. In a neighborhood located in the outskirts of La Habana, in the outskirts of Las Américas, in the outskirts of History, in the outskirts of Humanity.

Her name is, of course, María. And I was her baby-god, born accordingly in December. Devoid of apples, but still avid of her breast milk. Christmas were prohibited in those sweet seventies of socialism, the sour seventies of socialized fear. Tradition then meant resistance. Resistance then meant nothing but private love. In a country where private things were considered a crime.

In my childhood dream we find ourselves in another country, when another country meant exclusively the United States. I dreamt in English, of course, before the discovery of English thanks to my dad. Before the early discovery of death, of course, thanks to my dad too.

The United States used to appear devilishly dim in that dream. Cuban children were all afraid of those two words: Estados Unidos. Halfway between ideology and idiocy, we, the children of Castro, dreamt the United States as a magnificent but maleficent remix of murder, money, mafias, and many other miserable miracles. In my dream my mother María tries to wake me up with a nana this time sung to me in English, a tongue we both ignored in December of 1971. Hush now, baby, baby, don’t you cry. While her sweet young face turns into the face of an unspeakably unknown old woman, with a sinister smile. Mama’s gonna make all your nightmares come true.

Many decades after that winter, in a new century and millennium, that little baby fed by Mary of God in La Habana has suddenly become a writer who wanders like an orphan all around the bedrooms of the real United States of America. In 2017, having unavoidably become a grown-up, this man, who shares with me my own name and his childhood dreams, now only aspires to ungrow-up, like a Peter Pan in reverse. Or like another expatriate enfant-terible, behind whose mask, as Reinaldo Arenas called himself in a poem, lies the ghost of “child with his dirty round face.”

Every Cuban exile is at some point shocked by the writings of Cuban ex-exile Reinaldo Arenas. Arenas is not an exile anymore, because he put an end to this condition in December 1990. The Cuban Diaspora sometimes seems to be a hyper-realistic succession of successful suicides.

In his novel-apoteosis The Color Of Summer, Arenas’ literary legacy becomes an anthology of dreams. Dreams dreamt in Cuba and outside Cuba, but always about Cuba. As many in his generation, Arenas was HIV-positive and rapidly developed a mortal variant of AIDS. Yet, as he laid dying in a hospital of New York, he kept on dictating the colorful sounds of his sensational summer.

Arenas was diagnosed in 1987. Three years later we find him finishing his agonic autobiography Before Night Falls, much later to be adapted in a film by Julian Schnabel. And he was also dictating to his remaining friends and lovers, every time fewer and fewer as Arenas’ health deteriorated, the tragic-comic carnival of The Color of Summer, with its one thousand-and-one characters, including Fidel Castro as well as most Cuban writers on the Island and in Exile, a faustic and caustic feast which is one of the saddest testaments in the history of Cuban literature. And in the history of Cuba as well.

Many of those turn-of-the-old-century “impossible dreams” of Reinaldo Arenas are now the turn-of-the-new-century parallel dreams of Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo, flashbacks from the Cuban debacle that, as a neo-exile myself now, I keep on sharing as if they were my own dreams, thus becoming a virtual vandal, posting dream after dream without due credit in my @OLPL Twitter account (for me, this is not plagiarism but coalescence, co- adolescence):

I dreamed of a cataclysm. I dreamed of a bench alongside the ocean where I’d go in the evenings and just sit. I dreamed that I turned on the faucet and there was water. I dreamed of a pair of comfortable false teeth. I dreamed of a typewriter with an Ñ. I dreamed of an almond tree growing in front of my house. I dreamed of a river with green water that said to me: Come, come, here lies the end of your desires. I dreamed that a naked angel came and carried me away. I dreamed of a city like the one I lost, but free. I dreamed that all the horror of the world was a dream.

Sleepless in the last stages of his back then quite mysterious disease, Arenas knew that “there will be no rock, or doorway, or tree, or shrub that will not be fuel for our desolation and despair,” and he was well aware of “the merciless certainty that there is no escape. Because it is not possible to escape the color of summer. Because that color, that sadness, that petrified flight, that sparkling, gleaming, glaring tragedy ―that knowledge― is us.” That’s why he finally asked to a god in whom he had never had faith: “O Lord, don’t let me just melt away in these interminable summers. Let me be a meteor-like flash of horror that comes and is gone forever…”

Arenas confessed in Before Night Falls6 that “writing is not a profession, it is a curse” (256). During his ten years outside of Cuba he “realized that an exile has no place anywhere, because there is no place, because the place where we started to dream, where we discovered the natural world around us, read our first book, loved for the first time, is always the world of our dreams.” For him, “the exile is a person who, having lost a loved one, keeps searching for the face he loves in every new face and, forever deceiving himself, thinks he has found it,” so that “in exile one is nothing but a ghost, the shadow of someone who never achieves full reality. I ceased to exist when I went to exile; I started to run away from myself.”

Caribbean runaways, painfully running away from ourselves. Is this definition of Arenas ‟Cuban-ness” appropriate enough for the legion of Cubanologists that pry upon the archives of Cuban literature, which practically can only be accessed from outside Cuba, for on the Island of Treasure nothing is treasurable anymore?