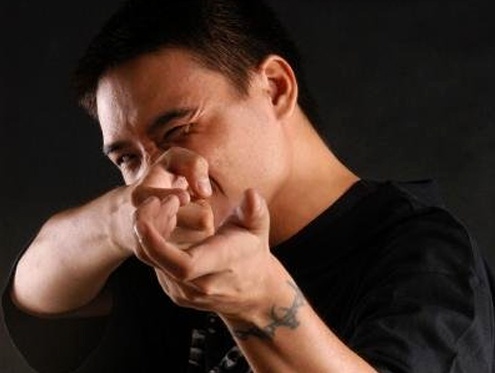

Burmese Rapper Zayar Thaw: A Left Hand of a Boxer

by Khet Mar / September 26, 2011 / No comments

In 2000, the hip-hop group Acid, of which the popular Burmese rapper Zayar Thaw was a part, released Burma’s first hip-hop album. Despite predictions of failure by many in the Burmese music industry the album stayed at number one on the Burmese charts for more than two months.

Zayar Thaw is also one of four founding members of Generation Wave a pro-democracy youth movement opposed to Burma’s military government, that started in October 2007, following the anti-government protests popularly known as the Saffron Revolution.

Before he was arrested in 2008 Zayar Thaw was combining his music and social activism to perform charity concerts for orphans with HIV. He also visited the orphanages, looked after the children, and helped to teach them English with fellow Burmese rapper, Nge Nge.

Zayar Thaw was arrested with five of his friends in a restaurant in Rangoon on March 12, 2008. He was charged with forming an illegal organization—Generation Wave—and sentenced to six years in prison. He was allegedly beaten during his interrogation. Ten minutes before Zayar Thaw was sentenced, he wrote a statement which was leaked to Generation Wave members. “Tell the people to have the courage to reject the things they don’t like, and even if they don’t dare to openly support the right thing, tell them not to support the wrong thing,” his statement said.

On 20 November 2008, he was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment for illegally organizing under the Unlawful Association Act; Zayar Thaw was given an additional year’s imprisonment for possession of foreign currency. He served his sentence at Kawthaung prison and was released on 17 May 2011.

Since his release, he has participated in many social and political activities including performing at Burma’s pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s 66th birthday party. Aung San Suu Kyi even mentioned Generation Wave in her 2011 Reith Lecture on BBC.

In August 2011, Zayar Thaw was banned by a police station from performing at a fundraising concert for a senior home in Rangoon (Yangon). I interviewed Zayar Thaw via email a week after he was banned. In this conversation, Zayar Thaw talked about the advantages and challenges of including political content in his songs and in Generation Wave’s activities. He also talked about his feelings on the non-violence movement and delivered a message to international readers.

What do politics mean to you?

Politics are defined in so many ways. As for my own opinion, politicians are irresponsible and are only concerned for the small ruling group or administrative personnel. It directly affects those who are living in that country. The government’s policy and its lawfulness, as well as its people, play a major role in the promotion and development of that country.

Why did your album Beginning become so popular?

When Acid started to compose that album, our objective was very clear and simple: We are crazy about hip-hop music and wanted to listen to it in Burmese. We didn’t want to become famous, successful, earn money, or even to be talented musicians.

Until that time there was no real hip-hop music in Burma except for some people who would sing small rap verses in other songs. Some people accepted us on a certain level. However if one thinks we’ve succeeded, it’s because of our craziness for this new kind of music in Burma. Its success would also be because of support that the youth has for new things and creative ideas.

What are the advantages and challenges of including political content in your songs and activities?

As you know, we (Acid / Generation Wave) compose and create music with a political context. We also take some action on those topics, within our capacities. We create songs that relate to politics, not only in lyrics, but in their composition and performance as well. We play as often as we can, passionately, and always try our best. One distinct achievement is the support we’ve received from the youth of Burma. These activities increase their awareness of current political situations in Burma. However in our country, with no basic human rights, such as freedom of speech and freedom of expression, our activities have been accused as crimes and some of us have been spending time behind bars.

What other activities did Generation Wave organize before you were in prison? How effective were they?

First, I would like to explain that Generation Wave is a young activists group. There are musicians, but most of the members are artists, like poets and graffiti artists. Not only does Generation Wave organize specific musical activities, but we also take part in other political activities and campaigns, to make people aware of politics in Burma and help inspire them to be socially active. As far as effectiveness is concerned, I can emphasize it with our slogan, “We are the left hand of a boxer, but the people do the knockout.” The activists in Generation Wave try to expose the feelings in peoples’ hearts and stimulate them to mobilize those feelings. However, getting the people to participate is our ultimate goal.

What happened with Generation Wave after your incarceration?

Actually, Generation Wave was founded by four of my friends. Although my friend and co-founder Aung Ze Phyo and I had been incarcerated, the activities continued with the guidance of the remaining leaders.

Generation Wave’s video. October, 2010.

You took the risk of being slapped with a longer prison term and released a well-known statement ten minutes before you were officially sentenced in 2008 . What made you write this statement?

At that time I already knew that I wouldn’t have a voice for a certain number of years. At the last minute, I expressed my sincere feelings and said that I want people to be brave and not be afraid to speak their minds. I released that statement to the public, especially to the youth, to encourage them. When I did this, I was aware of what might happen to me, but I thought that I should do something for our people as a duty for their future activities. I did it without any influence or concern for the consequences.

Political prisoners in Burma are tortured without compassion. When they tortured me I repeated to myself, “This awful time will not be forever, this is going to end soon.” “I don’t have to say any name of my network.” How did you face that terrible experience?

I accepted that experience as the result of the evilness of others in my life. It is unforgettable. I do believe that if you have a deep-seeded way of thinking and strong beliefs— and you made a clear decision based on those beliefs—then you are ready to face anything for your rights. Your insight, willpower, and natural courage will transcend.

What did you reconsider about your social, musical, and political life while you were spending time in prison? Did some of your thoughts change?

I do have the habit of reflecting upon my actions from time to time, not only when I was in prison but also in my daily life. While I was in prison, I reconsidered some of my past actions and I felt very uneasy about it. I don’t feel that I’ve used my full capabilities to help the country as well as the people. So I decided that I would act more for them when I was released. At the present time, I try my best, although this doesn’t totally fulfill my desire.

According to a survey done by Freedom News Group—a media outlet created by Burmese human rights organization—83 percent of the youth in Burma would like to see you as a political leader. Are we going to see you as a political leader?

A political or national leader, whatever it may be, cannot be declared by himself or herself. The role of leadership will be decided by the people according to his ability, his conducts, his capability, his loyalty, and his managerial skills etc.

Hypothetically, would you lead under the principles of non-violence?

I do believe in non-violence, simply because I hate violence. To quote Mahatma Gandhi, “Non-violence is the greatest force at the disposal of mankind. It is mightier than the mightiest weapon of destruction devised by the ingenuity of man.”

Since your release you have participated in some events organized by the National League for Democracy (NLD)—Aung San Suu Kyi’s party. You sang at her birthday celebration and have been her bodyguard on some of her trips. However, you are not an NLD member. Why you are not a party member?

As a political activist, I’m not really concerned with becoming a member of the party. One needs to be persistently aware of the people’s benefit, as well as the rights that one believes in. I have been in Amay Suu’s (Mother Suu) personal security group because I admire her and adore her as my role model.

You are banned as a singer. What does this mean for your future?

As a musician, I will continue to write my compositions when I have the chance, whether I get to meet my audience or not. For example, I wrote and recorded a new song for the youth on Amay Suu’s 66th Birthday Tribute Album. As for banning me as a public singer, I take it as the Authorities doubly punishing me. This just highlights the lack of freedom of expression in Burma.

What do you want to say to readers who are going to read this interview?

Burmese people want to be ordinary people who live peacefully and simply in their daily lives. We are not asking for a more-than-normal-well-being with aggressive and greedy desires. We are demanding our basic human rights, which people in every part of the world have. I want you to know that Burmese people are still struggling and suffering under the oppression of its rulers in southern Asia, while people in other parts of the world are freely discussing and arguing about their future plans and other activities. If you realize those conditions and it makes you feel compassionately towards us, than I am very thankful for this interview.