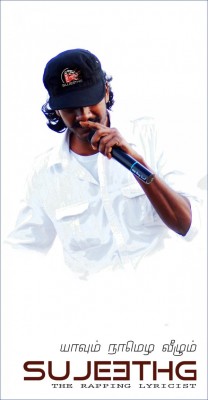

Tamil Rapper SujeethG: “The search for fame and saleability spells the end of social concern.”

by Meena Kandasamy / July 25, 2011 / 1 Comment

UK-based Tamil rapper SujeethG‘s lyrics deliver stinging commentary on societal evils, and his pulsating anger stands up against all forms of oppression. His raps echo the valorous beats of centuries-old Tamil war epics even as they seamlessly switch to Eelam Tamil street slang, as heard on the streets of Tooting. A prolific artist, SujeethG has released more than 60 songs, including four albums: Singles (2005), Adi Mel Adi (2007), Anayaathu (2010), and Raavannan (2011). He has also written and directed a short-film Paavam (Sin, 2010) reflecting the difficulties of the Tamil Diaspora.

In this interview with Meena Kandasamy, SujeethG speaks about his work, the importance of protest music in a revolutionary struggle, and rap’s ability to transform the meaning of the material it appropriates.

You work with all genres of music, but you seem to identify yourself primarily as a rapper. Why?

I heard rap music only after I came to London, and it captivated me. I started rapping in Tamil when I realized that it was a great medium to reach out to the second generation of the Tamil Diaspora. I had been a columnist, writing essays and social commentary, but I wanted to connect with the youth who were at the forefront of our struggle.

Rap held a stronger appeal for me than any other form of music. It energizes the listeners because it has a certain spontaneity, and it is almost like a form of speech. I think of rap as a solid medium to express social concerns and voice out against all forms of oppression. Rap has been heavily appropriated by corporate media, but I want my music to move beyond the standard formula of drugs, guns, gangsters, and girls.

It sounds nice and radical to say that rap lends itself as a tool to protest oppression. Have you used it that way?

I don’t think anyone can escape politics, certainly not someone from my generation or background. So when I realized my talent for rapping, I wanted to make an impact on the Tamil-speaking people who number about 80 million worldwide. So, since 2006, I have released more than a dozen songs as singles about the oppression against Tamil people in Sri Lanka. My intention was to raise awareness among young Tamils in the Diaspora about the sufferings undergone by our people and the need for resistance and solidarity. Later, these songs were compiled as Anayaathu. This album was released on May 18th, 2010 to mark Mullivaikkal Remembrance Day in memory of the hundreds of thousands of Tamil people who had perished in Sri Lanka the previous year. All proceeds from the sale of my album went to charity.

How have Tamils received you as a rapper?

Young Tamils from diverse backgrounds are my fans. Honestly, in 2005, the first comment from middle-aged viewers of a Tamil television channel was: “Why is he shouting like a black man?” My song “Viduthalai” (Freedom), released in 2006, had a strong message against oppression. When that was released, the elder generation started to accept my work. They saw me as a powerful voice of protest. I have earned their respect, but I am not sure if many of them appreciate rap or listen to it repeatedly.

Sri Lanka has established a reputation for curtailing media freedom. As a Tamil from that war-torn island now living in London, can you comment on the absence of freedom of expression in Sri Lanka?

It is dangerous to be a creative artist in Sri Lanka because it is a hidden dictatorship. That is why writers, artists, journalists, and filmmakers are fleeing the place. This is not a new thing because alternative opinion has never had any space in Sri Lanka. Forget writing a revolutionary article; if a Tamil schoolboy is caught looking for the politics page in the newspaper, he would be in trouble. This has been the situation for several decades. You can be a leftist, but you will be asked to compromise with the right-wing forces if you want to stay active in politics. The only positive outcome of writers and journalists in exile is that we have the chance to present the true face of Sri Lanka before the international community.

Tamils in Sri Lanka today cannot take the risk of using art for revolution. And yet, we need a culture of resistance in order to carry our struggle. Art affords a choice, allows people to speak out. Within Sri Lanka, music cannot be used publicly for resistance in the present context.

In their early days, the Liberation Tigers made use of art to a great extent —and more particularly, music— to make an impact on the Tamil people. The same strategy continues to be used in the Diaspora. I often hear from fans and friends of how my songs are played at protest marches and Tamil demonstrations everywhere, whether it is in Geneva or Toronto. I am happy to contribute to the upsurge and resurgence of Tamil people. What is happening in Sri Lanka is a planned and systematic elimination of Tamils from the island. Not only are Tamils being killed, but their cultural symbols are also being destroyed. Because of the near-total lack of freedom of expression in Sri Lanka, the safety of staying in a foreign land gives me the responsibility of speaking about the suffering of my people. Let the world open its eyes and look at us.

With the much-touted “end of terrorism” on the island, do you think Tamils in Sri Lanka face a better future?

Though they were seen as terrorists by the world, the Tigers were the only resistance to Sinhalese oppression. Today there is no one to speak up for the Tamils. At present, we are a silenced minority in the island.

Now Sri Lanka projects itself to the outside world as a tourist destination devoid of terrorism. They are selling the myth that there is peace for everybody but nothing can be farther from the truth. The root of the problem lies in the absence of equal treatment. Unless that problem is sorted out, I wonder whether lasting peace can ever come to the island. Even the Sinhalese soldiers who died in the civil war were only victims of a poverty draft. They had no knowledge of the struggle, they only believed in the propaganda that Tamils were immigrants from India.

One must realize that the Tamil revolutionary struggle is not against the Sinhalese people. It is against the chauvinistic ruling Sinhala classes who deny rights to Tamils. The formation of an independent homeland would not in anyway distress the Sinhala people, but the supremacist thinking and hegemonic Mahavamsa mindset that sees Tamils as second-class people is prevalent among Sinhalese politicians in Sri Lanka. That is why they don’t want to give equal rights to the Tamils.

You seem to clash head-on with myths. You blame the Mahavamsa for the Sinhalese mindset. Likewise, when people normally look at Raavannan as a defeated hero from the epic Ramayana, you name your latest album after this controversial character. Why?

There’s no denying the fact that people keep going back to myths all the time. The hegemonic mindset cultivated by epics like the Mahavamsa –which portrays the Sinhalese as the native inhabitants of Sri Lanka and the Tamils as latter-day immigrants from India– is responsible for the situation prevailing in Sri Lanka today. The Sinhalese believe that the island belongs only to them, and that we are foreigners staking a false claim.

Likewise, the Ramayana is a part of the Tamil syllabus, and unknown to ourselves, we are made to read a religious text that portrays us as horrible people. I look at the Ramayana as a myth that was written to push a certain supremacist Aryan agenda. As a man from Lankapuri (present-day Sri Lanka is referred by this name in the Ramayana), and mainly as a Tamil, I see Raavannan as a Tamil icon of resistance against oppression. Valmiki’s Ramayana depicted the north-Indian Rama as an avatar of god, south Indians as monkeys and the people of Lankapuri as demons. I named my album after the King of Lankapuri because I did not agree with his portrayal as a villain. There is a long history of challenging the Aryan agenda of Ramayana. The title song “Raavannan” is based on this issue. I find the resonances of the epic strongly even in today’s context, and I think every Tamil should be aware of this.

You criticize the superstitious beliefs of Tamils. Why did you address this theme?

Tamil people take their religious identity very seriously. For once, why don’t we look at this from God’s perspective? Everyone is asking for favors. So it is all about making deals with him. One of my songs “Kadavul” (God) deals with how God has become a security guard and “O.Saami” (O’God) deals with how there exists a big group of brokers between people and God. I want to awaken individuals from such blindness. For instance, “Kozhai” (Coward) from [the album] Raavannan challenges male domination.

I am now working on Pambal (Fun), slated for release in 2012. This album is totally funny and humorous; it marks a switch from a serious trend towards light-hearted comic satire. As usual, my friends Santhors and Thishanthan are composing the music for this project. In this album I also deal with social issues like dowry deaths and caste oppression. I think it is important for us to not only criticize our oppressors, but also to think within our own community and work towards righting the many wrongs we see.

How do you feel about the corporate commodification of music?

My music is not molded by the market. The corporate world looks at sales and audiences; it begins dictating terms. However, my music is concerned about the message it puts across. I believe that pursuing any kind of a corporate agenda prevents the creation of true art.

In the context of the Tamil language (in which I work), the music industry simply functions as an extension of the movie industry. In such a case, an independent artist like me has to resist the pressure of writing formulaic lyrics for commercial films.

The elusive search for fame and saleability, instead of looking at the value of ones creation, spells the end of social concern.

RELATED ARTICLES

Listen to more of SujeethG’s music.

Watch the documentary Killing Fields on the genocide that took place in Sri Lanka.

Read Sampsonia Way’s interview with Indian poet Meena Kandasamy.

Read Sampsonia Way’s interview with filmmaker Leena Manimekalai.

One Comment on "Tamil Rapper SujeethG: “The search for fame and saleability spells the end of social concern.”"

Nice blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere?

A theme like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my

blog stand out. Please let me know where you got your design. Cheers