Passa Porta Festival On the Move

by Silvia Duarte / March 31, 2011 / No comments

Passa Porta is Brussels’s international house of literature. Passa Porta is a meeting place for readers and writers, a space where the link between Dutch, French, and foreign-language literature is reinforced.

Every two years, Passa Porta directs its Literature Festival in collaboration with many other local and international partners. From March 24th to 27th Brussels beats to the rhythm of the Passa Porta Festival: four days of meetings, discussions, and festivities, attended by more than 8 thousands lovers of literature.

The theme of this third festival was On The Move:. “Moving, leaving, traveling, losing the way, and escaping… Whether man is a nomad or not, an adventurer or an exile, he is constantly on the move by force of habit, out of curiosity, necessity and love. In total liberty, but often under duress too…” states Passa Porta’s website.

The festival reached its climax with a grand literary tour in the city center on Sunday March 27th. Throughout the day, more than 8 thousand literature fans were treated to 100 encounters and talks with a wide range of authors in theaters, bookshops and libraries, as well as in cafés, churches and train stations.

The international guests included Philippe Claudel, Péter Esterházy, David Mitchell, Jean-Philippe Toussaint, Sandro Veronesi, Douglas Kennedy, Mathieu Amalric, and Juli Zeh.

In this interview, Paul Buekenhout, Passa Porta project coordinator, talks about this great and sui generis project.

What have been your biggest achievements in all these years of the festival?

We are now able to serve audiences that speak different languages. For me, that is a major achievement. It is important to represent different languages here. Brussels is a multi-lingual city; it is a multi-cultural city. All of these cultures have their own networks and activities, but with the Passa Porta Festival we try to bring them all together. And it is working. It could be better, but so far we are doing a great job, if I may say so.

So, you are offering a kind of passport from one culture to another culture…

Exactly. Yesterday (Friday, March 25) there was quite a mix of cultures and languages present in the theater—not just on stage, but also in the audience. I love that.

Voyage autour de chez moi. A multi-disciplinary travel report about weeks’ expedition around the Beguinage church. Testimonies and life stories were jotted down in a caravan. Photo: Antonio Pistis

Is the mix of languages what makes this Festival sui generis around the world?

Yes. The multi-linguism of this festival is a characteristic that sets it apart from other literary events. In Scotland there is a huge event called the Edinburgh Festival of Literature. It is bigger than ours, but every author speaks English, and the audience is composed primarily of English-speaking Brits and Scots. Anyone who doesn’t understand English is lost. That’s not the case here.

Here, we communicate in Dutch, French, and English, and at the festival events themselves there are about 15 different languages spoken. Last year I believe there were 22. That is different from the other festivals, and it’s the main characteristic that sets us apart.

Another aspect that makes our festival unique is the amount that we cooperate with other organizations. Whereas most other festivals work with one, two, or three other partners, we cooperate with dozens of organizations. Our festival is not perfect, but I think we are on the right track.

Are only writers invited to the events?

It has to do with the theme. Right now because the theme is On the Move we have a lot of writers who are travelers, non-fiction writers, philosophers and also journalists. Politicians are invited only on the condition that they work with our team. We won’t give a forum to a politician just like that.

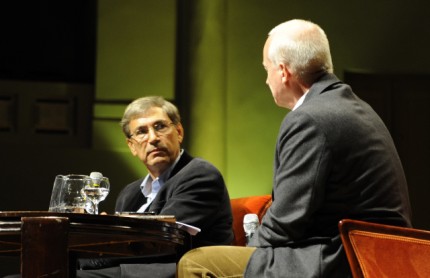

Orhan Pamuk. The festival closed with the Turkish Nobel prizewinner Orhan Pamuk, who reflected on the theme On the move. Photo: Katriene Degreef

Why is this festival important to Brussels?

This festival is important for the city because, in a way, Brussels does not have a good reputation. Abroad, Brussels is considered a kind of phantom city; a city where big decisions are made by phantoms; the neighborhood where the European Parliament is located; a kind of rich ghetto—it’s a fortress. People don’t have much sympathy for this. But Brussels has much more things to offer. The festival is the best marketing campaign that the city has ever had.

What was the most difficult obstacle you confronted during the organization of this festival?

Well, there are more than 120 authors coming, which is quite a lot. Every author has to be invited, and of course not every author accepts. So we have to invite about 200 authors in order to end up with 120. A lot of work goes into this process. After the invitation you have to brief them, find all these different venues and speak with all of these business partners.

You also organized international projects to present at the program; projects that have also appeared in great publications… Could you talk about them?

Last edition, we did the “European Constitution in Verse” project. The idea was that if politicians can’t or won’t give their people a constitution, then poets will create one in verse. We had about 52 poets—at least one from each European country—and not just European citizens, but also poets who live and work in European countries. A lot of ICORN and PEN writers, as well as refugees participated in the project. These 52 writers spoke about 30 different languages among them—minority languages included. And we had to translate all of it into French, Dutch, and English. There were more than 70 translators involved.

“Letters to Europe” presented on Friday in this Festival was a bit easier. We had 22 writers from different countries composing letters to Europe. We had to translate these as well. These are crazy projects. But they were splendid. All this is creation, and it’s difficult, but it’s very rewarding.

Read more about Sampsonia Way in Brussels