The Price Of Committing Journalism In Zimbabwe

by Elizabeth Hoover / January 18, 2011 / 2 Comments

Just this month, Zimbabwean police launched a manhunt for an editor accused of publishing a false story during the 2008 elections. Are hopes fading for greater press freedom in the country? Two exiled writers discuss President Robert Mugabe’s ongoing repression of speech.

In April 2008, New York Times correspondent Barry Bearak was arrested in Harare, Zimbabwe, for the crime of “committing journalism.” The Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter had been covering the elections, but, when the results weren’t what President Robert Mugabe expected, the secret police started rounding up reporters.

Mugabe has kept his grip on power since 1980 with vote-rigging and intimidation. However, in 2008, he found himself in a run-off with opposition candidate. In response, Mugabe deployed militias to beat suspected opposition supporters, kill resisters, and arrest journalists. “Elections can be held in Zimbabwe, as long as Mugabe wins,” Bearak explained to Sampsonia Way via e-mail.

Press freedom has been brutally suppressed since 2002, when legislations destroyed the independent newspapers and gave Mugabe control over the media. Knowing how the secret police monitors journalists, Bearak had been careful, but the demands of filing stories daily forced him to work in the open. “Necessity numbed my own caution,” he wrote in the New York Times in 2008.

He would spend 72 hours in jail, swatting cockroaches, trying to keep warm, and getting an “insider’s perspective” on the archaic and arbitrary justice system. “Mugabe likes to maintain this veneer of legality; the courts can apply the law unless he decides otherwise,” Bearak said via e-mail. He secured his freedom with the aid of human rights lawyer Beatrice Mtetwa, who has survived multiple beatings by police. According to Bearak, police officer told Mtetwa they wanted her to experience the brutality she protested.

It turned out “journalism” was no longer a crime. “The magistrate considered the charges a bit laughable,” Bearak said. After he was released, he fled across the border, but has been unable to return since new charges against him have been concocted. Because of this, he preferred not to comment on the current situation inside the country.

“This exclusion from Zimbabwe is very painful for me,” he said. “I am unable to report on a story that I considered then, and continue to consider now, the most compelling in the region.”

The elections eventually resulted in a power-sharing deal with Mugabe as president and Tsvangirai as prime minster. Under that agreement, the government pledged media reforms and independent newspapers have resumed publishing. However, Reporters without Borders calls the situation “fragile.” After their publications hit the stands, editors and journalists are arrested, threatened, and accused of leaking state secrets. Just three weeks ago, the police issued an arrest warrant and launched a manhunt for the editor of the Zimbabwean, who they accuse of publishing a “false story” in 2008 about the alleged murder of an election official.

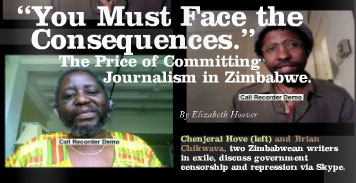

“We have freedom of expression; what we don’t have is freedom after expression,” is how author Chenjerai Hove described the situation in Zimbabwe. Currently, Hove is a writer-in-residence in the Miami: City of Refuge, a project coordinated by the Florida Center for the Literary Arts at Miami Dade College with the financial support of the Knight Foundation. Hove is the author of four books of nonfiction, two plays, and four novels, including Bones, winner of the 1989 Noma Award for Publishing in Africa. He left the country in 2002 to avoid arrest after refusing government bribes.

By the time he left, Hove was considered a major voice in Zimbabwean literature and admired by young writers, such as Brian Chikwava. Chikwava first read Hove as a student in Zimbabwe and the two of them met after Chikwava moved to London and established his own reputation as the author of the critically acclaimed novel Harare North.

They came together with Sampsonia Way via Skype to talk about the situation of writers in Zimbabwe. After facing technical difficulties, the conversation was completed over e-mail. Here are the perspectives of two Zimbabwean exiles from different generations on Zimbabwe’s uncertain future, resilience of the writer under oppression, and the broken promise of liberation.

What is the situation like for press freedom in Zimbabwe?

CH: There is climate of widespread fear dating back to white minority rule. The fear has grown during Mugabe’s government and created a kind of viscous self-censorship.

During the 1990s I wrote my columns for The Standard and people would always ask me a terrifying question: “Are you still out?” I’d say, “out of what?” They meant the maximum-security prison. I was never arrested for those columns but everyone assumed I would be.

BC: When you were writing those columns did you think the authorities would eventually become more liberal or did you think they would come down hard on you?

CH: I knew it was considered dangerous, but the small space that I was creating was necessary. Those in power have to develop the capacity to face criticism. Silence creates real dictators in society.

Are artists censored in the same way as journalists?

CH: We have freedom of expression; what we don’t have is freedom after expression.

Once a police officer said to me, “You can say whatever you want but you must face the consequences.” Those consequences include imprisonment, torture, or disappearance.

BC: That’s true, but the authorities don’t spend as much time on creative writers because most people can’t afford books. If you’re a journalist, oh my god, the government really monitors you. This government thinks that you either work for or against the state. The government will tell you they have balance freedom of expression and the need to protect the state from both internal and external enemies. However that balance is always tilted on the side of the conservative elements.

CH: There are cases of artists being arrested. The painter Owen Maseko has been jailed because of his images of violence that the government denies. If he is found guilty he might go to prison for over 20 years. Most of the artists’ organizations have been infiltrated by the secret police, so they can’t defend Maseko. He is languishing alone.

Is there still a literary community in Zimbabwe?

CH: They are trying, but the problem is the publishing industry. In the 1980s, the publishing industry in Zimbabwe was the pride of the continent. Now, because of the economic disaster and the repression, they are unable to publish books. I was chairperson for the writers union for four years and we had a very vibrant literary community with events where young writers, like Brian, could meet experienced writers, hear readings, and participate in our debates. By the time I left, people were too afraid they to gather any more.

BC: There is still the Book Café, where creatives hangout, and people go for music, poetry, or theater. Nevertheless, in the audience there would be agents wearing dark glasses and the organizers stopped them from running amuck by having nice words with them and giving them drinks. When I left Zimbabwe, the number of agents in the audience was growing. First it was two, then four, then six.

CH: Those men in dark glasses follow people everywhere—meetings, home, church. For me, it was the worst torture. They used to keep two cars in front of my gate at all times.

Was the relentless surveillance part of the reason you left?

CH: I went through some very frightening experiences—a secret police car smashed into my car, my house was broken into. The last straw came when I was the president of PEN Africa and the government offered me a lot of money—I think close to $200,000—to take writers from around the world to Victoria Falls so they would exalt the country. Of course I refused the money. Then the police accused me of smuggling drugs illegally to Botswana. I have never driven to Botswana! My informers in the secret police told me I should find a way to leave.

Brian, did you feel in danger as well?

BC: No, I’ve always been a coward and never said anything that would offend the authorities. I left at the end of 2002 because I felt isolated. If your work feeds off the creative community and that community starts to disappear, your mind starts closing down.

That reminds me of Chenjerai’s idea of “internal exile.” What does that mean?

CH: Since I was unable to engage freely in my country, I felt I was already in exile. For example, I was raising money for a school library, but couldn’t enter the school because the Ministry of Education didn’t approve it. A teacher invited me to visit and was suspended. There is so much fear because the government has infiltrated every organization, even families. There are families where the wife doesn’t know if her husband is a government informer or not.

Mugabe claims that Zimbabwe is a liberated country. What is your perspective on Zimbabwe’s liberation?

CH: I was heavily involved in the liberation struggle. When I was teaching in the countryside, I saw how the people sacrificed by feeding soldiers when they themselves had nothing. Then the leaders of the revolution monopolized and personalized the struggle. They think that people without guns didn’t contribute and that it is their right to rule forever, but in a democracy the right to rule is a privilege. Whenever you criticize the Mugabe government, they accuse you of not being grateful to them for liberating you. But I was not liberated by anyone. I liberated myself.

BC: There are young people, like the Green Bombers, who are very pro-government, but others think the concept of a liberated country has been monopolized by a clique of people who hold power. This skepticism isn’t just among the younger generation. When the liberation “hero” Welshman Mabhena died in October, his family refused to bury him in the national cemetery. They said he didn’t want to be buried among dishonorable men and thieves.

How would you describe the Green Bombers?

BC: They are a group of young people who serve as the foot soldiers of the government and intimidate opposition politicians to keep them from campaigning. They started as part of a scheme that the government said would give unemployed people training while learning the history of the nation. These youths only got brainwashed.

CH: They are paid according to the damage they inflict on government opponents. They have been destroyed by the system and it will be hard to reconstruct them into proper human beings with a sense of respect and dignity.

Moreover, they are part of a cycle of oppression dating back to the colonial days and through the white rule. Those structures of oppression, torture, violence, and intimidation haven’t been dismantled. Ironically, the Mugabe government kept the same hangman who hung members of the liberation army during the war. They increased the prison population to the point where there were more people in prison than in universities.

What are your hopes for the country?

BC: I hope out of the difficulties of the past 10 years, people emerge with a greater political maturity and can have a viable and self-sustaining democracy. Politics have turned out to be everybody’s problem.

CH: I want opposition candidates to run without their friends and relatives being tortured, or their wives and daughters gang raped in front of them.

What can the international community do to help change the situation in Zimbabwe?

CH: There are organizations like the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights who have the courage to defend victims of political intimidation and torture. They need financial assistance because they defend people for free.

How can writers like you create political change in Zimbabwe?

BC: Independently minded writers have the ear of the people who trust them over the propaganda machine that claims the nation is always under siege.

CH: Yes, writers also hold a mirror in front of society. When the country gets ugly, they record ugliness and when it gets beautiful, they record the beauty. We celebrated Mugabe as a hero because we were starved for heroes and writers must remind the people of the dangers of celebrating forever. I know one day I will go back to a truly liberated country, with the respect that every writer deserves. Then, as a writer, I’ll help people to say: We haven’t quite lost everything. As writers we can still sustain our vision and one day it will flower again.

Listen to Chikwava read an excerpt from Harare North

Listen to Hove read his poem ‘Flower’

2 Comments on "The Price Of Committing Journalism In Zimbabwe"

Great information 🙂

Trackbacks for this post