A Bellwether Banning: The Journey of Toni Morrison’s Beloved to the Banned Books List

by Sandy Fairclough / October 14, 2020 / Comments Off on A Bellwether Banning: The Journey of Toni Morrison’s Beloved to the Banned Books List

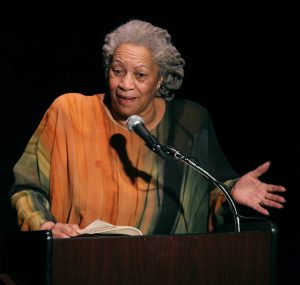

Toni Morrison speaking at The Town Hall, NYC, 2008. (Photo by Angel Radulescu)

Every banned book has its own unique trajectory towards censorship. In some cases, its author wittingly pushes boundaries like Vladimir Nabakov in Lolita. In other cases, like the evangelical right’s demonization of Harry Potter, the book is written with innocuous intentions only to be misconstrued as deviant.

If the lifespan of every banned book reveals something about its readers and the fractures in their culture, then perhaps no book’s trajectory is more telling of our current moment than Toni Morrison’s Beloved. The same themes of racial reckoning on the pages of Morrison’s novel are spilling into the forefront of our times. As we are observing the 38th anniversary of Banned Books Week, we are also protesting the continued police brutality against Black Americans and fighting an ongoing battle to end the whitewashing of American history. The need for freedom of expression is now more pressing than ever.

In a strange way — as sad as it may be — the ongoing inability of the American public to reckon with its history of racial inequity seems to echo Beloved’s journey towards censorship. It’s a book that’s been celebrated, ignored, and then celebrated again. It’s been snubbed and awarded, championed and vilified. It’s been given the Hollywood red carpet only to wind up banned from high school curriculums.

To understand Beloved’s journey as a banned book, we must return to the 1970s, when Toni Morrison was on a streak of true greatness, writing some of the most influential novels of the latter half of the 20th century. In the decade prior to her publication of Beloved, she wrote The Bluest Eye (1970), Sula (1973), Song of Solomon (1977), and Tar Baby (1981), establishing herself as a literary icon.

When Beloved was published in 1987, many felt it was snubbed for the National Book Award. Later it would land on “Banned” lists in the American South.

In September 1987, after a six-year hiatus from novel writing, Morrison published Beloved to high praise. Morrison’s exquisitely written prose is interwoven with magical realism and a ghost named Beloved, revealing the lived realities of racism in the wake of chattel slavery. The protagonist is a woman named Sethe, who has escaped a life of enslavement to live freely with her daughter in Ohio where they are haunted by the traumatic events of her past.

Despite producing another awe-inspiring novel, it took an act of protest for Morrison to finally receive the recognition she deserved. In the year following its publication, Beloved was nominated for the National Book Award, but it’s failure to win caused quite a stir among the literary community. Many felt that Morrison’s voice as an African-American woman had been purposefully snubbed. The frustration was so great that a group of 48 well-known African-American writers — including Maya Angelou, Angela Davis, John Edgar Wideman, and Amiri Baraka — signed an open letter protesting Morrison’s snubbing. The letter was published in the New York Times and praised the novel for being “[the] most recent gift to our community, our country, our conscience.” And while the aim was to put the literary community on notice while paying tribute to Morrison, it may have also helped convince the Pulitzer jury to award Morrison the 1988 Pulitzer Prize — giving her the mainstream recognition she rightly deserved.

Ten years later, in 1998 the novel was given another boost when Oprah Winfrey starred in the film alongside Danny Glover and Thandie Newton. At that point in time, you’d think the novel had secured its post in history. It had a Hollywood reception. The book was critically acclaimed. And so it’s with great curiosity that in another ten years, the book would find itself on a growing number of banned book listings throughout the American South. (One wonders, given the racial tumult that’s currently at the forefront of American culture, if the book’s journey was merely a forewarning of conflict to come.)

Alongside suppression of voice, there are many other reasons why books get banned in our country, from containing graphic subject matter, to being poorly executed, or being unsuitable for children’s education. In Beloved’s case, despite its obvious educational value, it often gets slammed under the guise of explicit sexual content and violence. This is precisely why, 20 years after Beloved’s publishing, despite its acclaim, Eastern High School of Kentucky replaced Beloved with The Scarlet Letter on its AP English curriculum. Suddenly, it was deemed too violent.

A similar situation occurred five years later in Missouri’s Plymouth Canton school district, when a hearing for Beloved was arranged after an uproar from two parents arose for similar reasons. Over 60 teachers, students, and parents attended the hearing, where the teachers who assigned the book argued for its place in the curriculum. While they commended the parents for wanting to watch out for their children’s education, they reminded those attending the hearing that AP students are self-selected, and highlighted the educational values of Morrison’s work. The ACLU of Michigan even went as far as to write a letter to the school district asking them not to ban it. In this case, the decision was reached that the novel could remain on the syllabus.

The most controversial case however, occurred in 2016 in the state of Virginia when Republican state senator Robert H. Black deemed the novel to be “moral sewage” and argued that it should be excluded from all English classrooms in Virginia. His disregard for the book was so great that he crafted a bill that would require all K-12 teachers to notify parents of any sexually explicit content within their reading materials. The bill would give parents the choice of opting their children out of reading said books. Interestingly enough, the same bill would allow parents to have their children opt out of sex education classes as well. The bill, dubbed the ‘Beloved’ Bill, was passed by both the Virginia Senate and House in February 2016 before it was vetoed by the state governor, due to the fact that the Virginia Board of Education was reforming similar policies and there was no need for a state law.

For many readers of Beloved, the moments in the book at which these bans take aim are not necessarily the ones that stick in their memory. And in fact, these moments in Beloved don’t seem to be even close to on par with other books that get banned for the same reasons (again, we’re looking at you, Lolita). The main point and plot of Morrison’s book handles something much deeper than a raunchy, sex-riddled tale; it means to illuminate a life experience that was a large, often untold part of history. To exclude the violence from the narrative would be an injustice to the voices that Morrison means to represent. The unflinching eye through which Morrison looks at the history of America’s South, and the violence that is an undeniable part of it might be a closer reason to why this book gets challenged. With the ongoing struggles to prevent American history from being whitewashed in classrooms, which we’ve recently seen in Trump’s attack on the 1619 Project, we can’t ignore the removal of Beloved from high school curriculums. It’s journey, it seems, is likely not yet over.

The ironic truth, however, is that banning a book puts it on the map. To hear that a book is banned these days piques curiosity and might cause more hands to reach for it on the shelf. So even as books continue to get banned, whether the disturbance comes from parents or from state senators, this counter-movement will always be here to give banned books a spotlight. Because, of course, curiosity is one thing that can never be censored.