A Life After Death

by Sonali Samarasinghe / April 27, 2016 / No comments

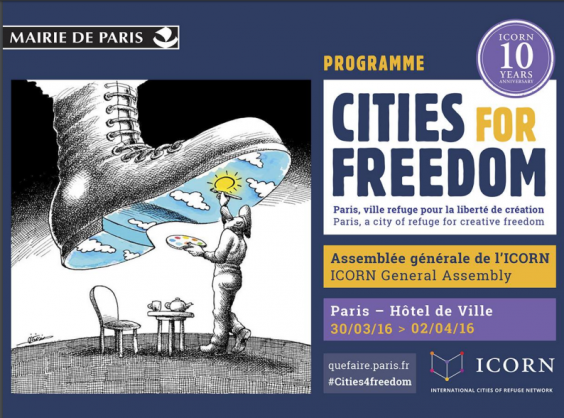

The following are Sonali Samarasinghe’s remarks to the ICORN assembly in Paris on March 31, 2016.

For me, the beginning of my ICORN story is not with tragedy, not with my forced exile, not with leaving my family, my country, my home, my friends and my familiarity to go to places that were unfamiliar, not where I had to start again to build friendships, to change my way of speaking, to change my metaphors, my references. It does not begin when I had to learn new skills, change my profession. It does not begin with my life in a shambles, but with hope. It starts with a promise that if we persevere, if we keep chipping away at the behemoth that is impunity and prejudice and hatred, we can still achieve something. This is what happened in Sri Lanka. This is what happened in my life.

- Sonali Samarasinghe

- Sonali Samarasinghe is a Sri Lankan writer, lawyer, and human rights activist. For five years she served as editor-in-chief of The Morning Leader, a national weekly, and as columnist for The Sunday Leader, a weekly openly critical of the government. The authorities targeted her and her family, and in 2009 she was forced to flee the country. In the United States she founded the website The Lanka Standard and completed a fellowship at Harvard’s Nieman Foundation and a residency at CUNY’s Graduate School of Journalism. Sonali Samarasinghe has been the recipient of many awards including the International PEN/NOVIB Freedom of Expression Award (2009) and the Human Rights Prize of the International Federation of Journalists. She is the current Minister Counselor at Sri Lanka’s Permanent Mission to the UN and ICORN writer-in-residence of the Ithaca City of Asylum in the United States.

So I begin by telling you that in Sri Lanka, on January 8, 2015 a war-weary people who had tolerated the assault on democracy to defeat terrorism, decided to fight for democratic freedoms once again. And just like that, the old political leadership was defeated in elections, ushering in a new era of hope and reconciliation. And all this happened exactly six years to the day my husband was murdered on January 8, 2009.

So you can imagine that for me, this surprising transition held special significance.

Because of our newspaper’s outspoken criticism of the regime, my husband Lasantha Wikrematunge, was assassinated in broad daylight, by a government-sponsored death squad. Two weeks later, facing death threats myself, I was forced to flee the country.

My husband’s car was surrounded by four thugs on motorcycles, who bludgeoned him to death while he was driving to work. I was supposed to have been in the car too, but Lasantha had told me to stay back to attend to a domestic aide who had taken ill. At first, the word of mouth news reported that I had been killed because most of the blood was on the passenger side of the car. A few months earlier, I had been followed by a white van, which had become a symbol of untold dread at the time. White vans followed dissidents, journalists and activists, terrorizing the streets and abducting those whom the authorities felt were against them. My home was also under surveillance, and neighbors had warned me that two men on a motorcycle had been parked behind some trees watching the house.

Immediately after the attack on my husband, I left my home and went to live with a friend under cover. Some of my own family and some of my friends didn’t want to even be seen in the same car I was in because they feared they would become collateral damage if I was attacked. I felt hurt and betrayed, although I understood their fear.

I left without telling many of my family members where I was going. My own mother didn’t know my location. I did this for her own protection. A few days after my husband was killed, two men had barged into my home demanding to know where I was, and even though my 80-year-old mother had protested, they had taken pictures of the interior of my home, and of her and of my little nieces. It was then I realized that it was not only me they were after. They could just as easily hurt my family in order to send a message to me.

I lived nearly four months in Europe before I eventually came to settle in America.

I want to highlight some of the changes and experiences I went through as an exile.

First, I felt a deep sense of betrayal by my own people.

Especially in the first few months, I was in shock and not actually processing what had happened or how much I had lost. So I followed any lead. And during this period, when one becomes almost childlike, it is so important to surround oneself with people who only have your best interests at heart. I lost my sense of discernment and judgment. I couldn’t tell who was a vulture trying to exploit my situation–and some did, including, it pains me to say, two journalists from Sri Lanka, one who surreptitiously recorded everything I said, feigning friendship, while I was in an utterly vulnerable state.

Thirdly I didn’t want to meet anyone Sri Lankan. Everyone seemed tainted and untrustworthy. The only times I allowed one of my own countrymen to talk to me on Skype (because that’s the only way I would communicate) it didn’t turn out well.

About two months after I arrived in America from Europe, I received a fellowship from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University.

Wonderful though the opportunity was, I realized that after being a prolific writer for over twenty years, I had lost my power of language. I suddenly could not articulate my ideas or my experiences well. I wondered whether anyone would even believe that I am a writer anymore. Here I was at Harvard University, and it seemed as though I was in this place of great learning and opportunity, at a time when I was least able to make use of it. It felt hollow and lonely.

At the time, I was not quite aware the extent of the impact of trauma on individuals. So it was only there that I began to learn how trauma disrupts the integration of the brain, and how our capacity to form representation is changed. We acquire abnormalities following traumatic experiences. According to scientists, one affected area is the left dorsal lateral prefrontal area of the brain, central to language. Those who have suffered trauma struggle to use words and cannot easily access language with the same facility as those who have not suffered trauma. Of course this ability comes back, but it helped to know that this was a real thing.

In addition to the sense of betrayal and my inability to write, I also began to become very possessive about my space. I usually love entertaining, but I began to lock the doors to my apartment and never invited anyone in. If the gas man knocked on my apartment door, I crawled to the door, locked it, rushed to the back door and locked that too, and would not let him in. I would sometimes get so scared of what was outside I would hide under the coffee table.

Secretly, I would yearn for the Sri Lankan feel of things. And because I refused to meet any Sri Lankans, the way I filled this yearning was through food and spices. I would eat mountains of rice and curry heavily spiced all the time.

But my residencies and fellowships, first at Harvard and then at City University in New York, were helping to build me up. I was making contacts, I was learning new things, like film, social media, and how to use these new tools. At CUNY I launched my own website, and I felt I had a voice again. Many other dissidents and activists wrote to this website. It became a voice for change.

And then, of course, I became the writer-in-residence at the ICORN City of Asylum in Ithaca. And it was there that I was able to really build myself up a lot more. This was important, because I had a support network and a city that embraced me, and made me feel at home. And so, more than even the other two residencies, I now began to actually make friends, go to the theater. I began a new career as an adjunct professor. I began to lecture, I formulated my own syllabi, and continued building up, learning new skills all the time.

And while one is are in it, going through so much pain, one doesn’t quite realize that you come out of all this immensely enriched in every way as a human being.

So I will now end with the beginning. On January 8, 2015 things changed in Sri Lanka. After six years in exile I was able to return to the country of my birth without fear.

My house, unoccupied for six years, looked like a sick child. As I began to attend to repairs and nurse it back to health, I found great empowerment and strength in the process. I was finally reclaiming what I had lost. There was restitution in feeling the soil of Sri Lanka under my feet. There was resurrection in speaking my Sinhala language, laughing at inside jokes, conversing in the spectacularly colorful colloquial Sri Lankan English. There was redemption in meeting my friends again; recompense in just being able to walk down the street without fear. There is healing still to be had, but the hope I saw on the faces of the people was inspiring.

In 2009, when they killed my husband, we had only been married two months.

In 2009, I was a bruised human being. Today, I’m okay. A lot of that has to do with the City of Asylum in Ithaca and my time there.

In 2009 I was devastated. I had no home country, nowhere to go. Today I have two home countries: Sri Lanka and America.