Is National Reconciliation Finally Possible in Burma?

by Ma Thida / December 2, 2015 / No comments

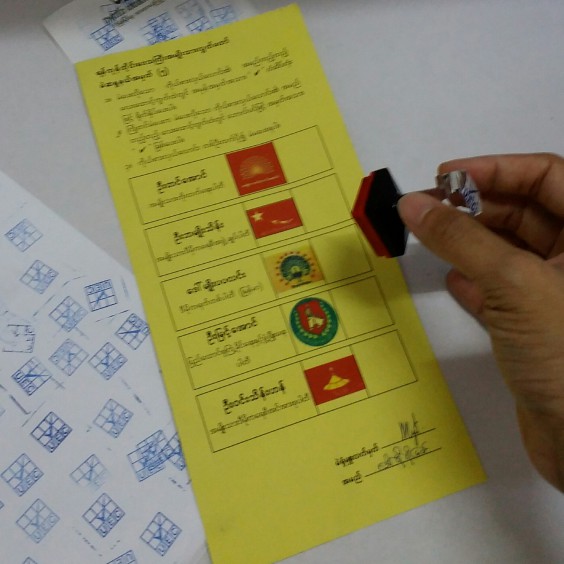

A ballot from the 2015 Burmese election. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Analysis of election results from Burma’s November general election reveal that national reconciliation may finally be on the table.

As soon as the Union Electoral Commission (UEC) announced the parliamentary results in the November 8 election, the National League for Democracy (NLD) was assured that it could nominate two vice presidents: one on behalf of the House of Nationalities, and one on behalf of the House of Representatives. (According to current results, NLD Members of Parliament hold nearly 79 percent of the 75 percent of civilian seats in the House of Nationalities, and 80 percent of the 75 percent of civilian seats in the House of Representatives.) However, according to the 2008 Constitution, the Army reserves the right to nominate another vice president, who could be elected as president of Burma. (Note that the Commander-in-Chief still retains the right to appoint the Ministers of Defense, Home Affairs and Border Affairs.) Afterwards, Aung San Suu Kyi, who remains barred from the presidency under the 2008 Constitution, said she would lead the new government with the aim of national reconciliation.

- Literature is an echoing voice of people’s thought. Myanmar literature and media have suffered a lot along with people during five decades of censorship. The majority of Myanmar’s population are voiceless, and many untold stories are yet to be discovered by local or international writers and journalists. Here let’s try to find and listen to what problems people are feeling, thinking, and facing regarding freedom of expression in everyday lives in Myanmar.

- Ma Thida is a Burmese human rights activist, writer, medical doctor, and former prisoner of consciousness. In 1993, she was sentenced to twenty years in Burma’s Insein Prison for actively supporting the Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. She served six years of her sentence, largely in solitary confinement and was released through the efforts of Amnesty International and PEN International. She has published nine books in Burmese and English, including The Sunflower (1999), The Roadmap (2011), and Sanchaung, Insein, Harvard (2012), a memoir. Ma Thida is currently president of PEN Myanmar.

National reconciliation had been seen as the most important objectives to make our society strong, stable, peaceful, and prosperous. The current government used this term to attract armed ethnic groups to its national peace process soon after taking power in 2011. The current peace process seeks to implement the National Peace Accord after a nation-wide ceasefire agreement and political dialogue. Since the beginning of the reconciliation process, many have criticized the process’ order. Most ethnic groups, especially armed ones, preferred political dialogue before a ceasefire agreement, while the Army and Union Peace Working Committee (UPWC) insisted on first signing the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA). The process went on under the Army’s framework, taking nearly five years to sign the NCA, and with the support of only eight out of the 18 armed ethnic groups.

The peace process also aimed to include not only armed ethnic groups in the political dialogue, but also political parties. Yet the role of political parties, whether ethnic or non-ethnic, was almost non-existent when the NCA was signed. Only one political party, the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), played a role in the NCA. However, the whole ceasefire process lacked legitimacy from the current USDP parliament, as there existed no bill of national reconciliation as of yet. In fact, President Thein Sein and the UPWC seemed to have no will to deal with parliament, run under Shwe Mann. Therefore UPWC tried to gain legitimacy only for the result for the first order of peace process: the NCA. Although leaders and most followers in both executive and legislative power of the current government are all USDP members, the enthusiasm, understanding, and commitment to the peace process vary amongst the president and his UPWC team, the Speaker of the Lower House of Parliament, and the rest of the USDP members. This means the ruling USDP party had never had any one strong perspective or plan to gain peace in Burma, and had also failed to make its strategy and plan adopted by every one of its member. On top of that, the NLD has had no role in the peace process as of yet.

In this situation, the NLD now carries a promising chance to form a new government of its own, and say they wish to make a government based on national reconciliation. Both NCA-signed and unsigned armed ethnic groups had shown their support to Aung San Suu Kyi and her winning party, the NLD. In that case, the army might be the most terrifying partner in this scenario. True or not, recent fierce armed conflict in the northern Shan and Kachin states are endangering thousands of civilians. Non-NCA-signatory armed ethnic groups partly control these areas. Therefore the people cannot be calmed down even though their favorite, the NLD party, won a majority in this 2015 election.

How can national reconciliation be possible? This is still a hard question. Certainly, there should be two different strategies to form two sets of governments: national and regional. For regional governments, in some divisions and states, such as the Magwe and Tanaserin divisions and Mon state, the NLD candidates won 100 percent of the votes. Analysts expect that the Arakan National Party ANP won 65 percent of votes in the Arakan regional parliament and Shan National League for Democracy (SNLD) won 25 percent in Shan regional parliament. According to the 2008 Constitution, both the country’s president and regional chief ministers could be any person with or without mandate. Appointing regional chief ministers is the privilege duty of the president. Since Aung San Suu Kyi said she will be “above the president,” many foreign and local analysts criticized her, but many people were reassured by the statement. Their concern is that if she cannot be the president and if the Army’s nominee becomes the president, executive power at both the national and regional level would not be changed.

On the other hand, long-term hatred towards the majority Bamar by other ethnic groups had been established by the civil war. Therefore many analysts guess that next government might bring some qualified — elected or not — persons from either ethnic political parties or ex-army USDP. Yet, no one knows how the NLD would form a national reconciliation government. Hopefully the NLD will learn a lesson from the USDP in terms of having a single strong, national reconciliation initiative, and making that accepted and practiced by every one of its members.

In this regard, we should also look at national reconciliation between government and people. Throughout our history, trust between the government and its people had been lost or violated because of militantly military regimes. In this November 8 election, voters proved that a party cannot win even a few votes without winning people’s trust. Our people desperately need a government that they can trust and love since they have a syndrome of hating and fearing “government.” People hope the NLD might be able to form a new government which could foster reconciliation between it and its people, with the mandate of an 80 percent voter turnout, and 80 percent of votes for the NLD.