Egypt Uprising: “I Never Thought It Would Start on Facebook”

by Amanda Cardo / February 10, 2011 / No comments

An Egyptian Protester’s banner. Photo: RT

In “Does Egypt Need Twitter?”, published in The New Yorker website on February 2, 2011, Malcolm Gladwell states that the human voice is a “largely unknown instrument” in today’s society and implies that the Egyptian uprising would have occurred even without the aid of social media.

Even though it’s clear that Twitter and Facebook are not gathering in Tahrir Square or protecting the museums and libraries of Alexandria, it is undeniable that they are an important aid in spreading the message of the Egyptian protesters. Here two Egyptians explain how the human voice has been a well-known and powerful instrument that is still in use—with or without the help of social media.

Speaking under pseudonym, Abdullah Al-Fulan, an Egyptian student on holiday in the United States, expressed his surprise at the origins of the January 25 protests: “I knew we needed a revolution, but I never thought it would start on Facebook. The youth was the engine for this protest and where else can you find young people getting together but on Facebook?”

Egyptian activist Abdelrahman El Hennaway, commenting from Cairo, added, “Facebook was a major factor to reach young people who don’t care about politics and don’t have serious economic problems.”

Photo: Egypt Social Media Cafe

Photo: Egypt Social Media Cafe

According to the CIA’s Factbook report from July 2010, only 25% of Egyptians have access to the Internet, and many of those who have it haven’t even been alive for the full length of Mubarak’s thirty-two year rule. It was June 2010 murder of 28-year-old blogger Khaled Saied that sparked the outrage of the formerly apathetic youth.

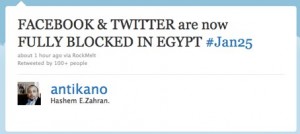

In January, risking arrest or worse, fans of the Khaled Saied Facebook page and other groups posted the whereabouts of riot police and locations of protests. Mubarak’s complete shutdown of the Internet on January 28 forced the youth to get creative in their efforts to protect and organize people.

The use of anonymous proxies and the donation of bandwidth to Egyptian servers from internet users around the globe allowed many to bypass the communication blackout that lasted until January 31. Sites like YouTube and TwitPic were inundated with photos and videos that allowed the Egyptian message to reach those outside of the territory.

As of January 31, “the game had gone out of Facebook,” said Abdelrahman, meaning that Facebook was no longer the primary source of information and instruction. “Picture and video sharing became very important,” he added.

The same day Google joined the social media fray by setting up a Speak to Tweet service in cooperation with Twitter. Those with access to telephone communication in Egypt could call a Google Voice number and leave a voicemail, which would immediately be posted as an audio file on the Speak to Tweet Twitter page. Volunteers dedicated hours to transcribing and translating the voicemails for international followers.

“I had no idea how to use it,” Abdelrahman admitted. “Didn’t meet anyone who did.” However, almost 3 thousand spoken tweets were posted, and this alternative method of tweeting eventually turned into a forum for longer-form expression. Speak to Tweet’s voice recordings were not confined to Twitter’s 140-character limit.

Still, this tool deployed by Google was only an extra aid to those thousands of protesting voices. Abdullah and Abdelrahman agreed that the greatest influence on the protests was the human voice. Thousands of people, formerly silenced by poverty, poor educational opportunities, and corruption, were not stopped by the lack of Internet or mobile communication; they still gathered in the streets of Cairo, Alexandria, Suez, and other Egyptian cities.

“Protesting was here long before phones or Internet were invented, so I don’t know what they [the Mubarak regime] were thinking when they blocked the Internet,” said Abdullah.

On one hand Abdelrahman and Abdullah testimonies seem to agree with Gladwell’s statements: This is not a Twitter or Facebook revolution, and it is unfair to the Egyptian people to say that it is. Facebook and Twitter are not sleeping in the streets of Suez.

On the other hand, Abdelrahman and Abdullah seem to contradict Gladwell. According to them, the human voice is a well-known instrument in Egyptian society–not the “largely unknown instrument” Gladwell claims it to be. They add, whether they use social media to help them speak or not, now they have a voice.