Jim Powell: “The Eggs Broken Were Millions of Human Beings”

by Elizabeth Hoover / October 27, 2010 / 1 Comment

The protagonist of Jim Powell’s debut novel The Breaking of Eggs, Feliks Zhukovski, has spent his entire life blindly loyal to communism. His stance is principled and uncompromising; it has caused him to distance himself from family, friends, and potential lovers. But, at age 61, this self-exiled Pole living in Paris is forced to consider his entire worldview as the Berlin Wall falls and communism crumbles.

In the hands of a less able novelist, Feliks would give communism the heave-ho, embrace capitalism, and move to America. But Powell refused easy answers. For him the picture is more complex, political labels are fluid, and no ideology is perfect.

While Feliks’ struggle is ultimately with ideas, it is tenderly rendered on a human scale as Feliks meets people who defy simple categorization, including his long-lost brother, a former girlfriend, and even a former French spy who tricked Feliks during the Cold War.

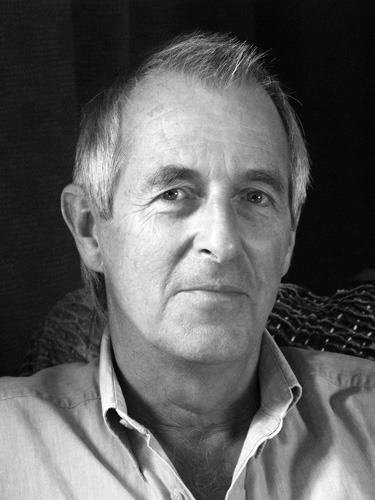

Powell is no stranger to new beginnings. He was born in 1949 in London. After careers in advertising, politics, and pottery design, not to mention a stint at an errand boy for the Beatles, Powell began writing a novel at age 50. He published his first, The Breaking of Eggs, at age 60.

In this interview with Sampsonia Way, Powell talks about the tragedy of communism, discusses the fallibility of government, and explains why Americans shouldn’t be disillusioned with politics.

You’ve said that your novel The Breaking of Eggs started with the question, “What is home?” In writing the book, did you arrive at an answer?

No, and I didn’t expected to because it can mean different things for different people. For most people it’s a physical place: a house, a neighborhood, a town, a country, but it can also be ideas or causes. Whatever it is, home is a very emotive word for everybody. I wanted to think about whether it was possible to get to be 60 years old and have no idea where or what home was.

Feliks, your protagonist, finds his home in the cause of communism. As communism is dismantled, he’s suddenly homeless.

That was true of a lot of people starting from the 1930s onwards as the news of the atrocities and terror under Stalin started creeping out from the Soviet Union. After that you were faced with a choice: deny that any of these things were happening, blame it on biased reporting, or say yes, these things have happened, they are atrocious, and there therefore has to be a complete revision of my thinking. A lot of people chose one of the first two.

But there were also a lot of people didn’t really choose. They didn’t altogether deny that terrible things had happened, but that didn’t make them shift their allegiance. Feliks is one of those. It is those people who gave the novel its title. Those sorts of apologists—the half-apologists—they didn’t deny everything, but they started to try and justify it, and the most frequent justification was: you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.

What do you think of that justification?

Well, it sounds quite homely, doesn’t it? Until you remember that the eggs being broken were actually millions of human beings.

When you want to change something, some group is going to lose out in that change. But what was unprecedented in Europe was the scale of that loss. It wasn’t just the number of losers, but it was also what they lost. Often they lost their lives, and if they didn’t lose their lives, they lost their liberty and any form of freedom we would recognize. You can’t say that was an incidental byproduct of this process. It was actually part of the process itself and was why communism was ultimately evil, if not in its intent, then certainly in its implementation.

Feliks seems able to overlook this because he’s not a deep thinker, at least in the first half of the book. He keeps saying, “I didn’t even think about that,” or “I’ve never considered that before.” Do you think that that kind of thinking is necessary to maintain an allegiance to an ideological system like communism?

Feliks would undoubtedly describe himself as an intellectual, but he’s an intellectual who puts huge fields of inquiry completely out of bounds. He’s convinced himself of something at a relatively early age and can give you all of the justifications in the world for it, but never actually thinks much beyond it. He starts to acquire an inquiring mind because he’s forced to when he meets people who have different perspectives and experiences from himself.

He does have several grains of honesty in him; if he didn’t it would be a very boring book because he wouldn’t change at all. But he is honest enough to actually start paying attention.

One of the people who forces him to reconsider his positions is his mother, who spent the war in Poland and then was sent to a forced labor camp under the communists. She writes him a long letter about her experience as a “prisoner of politics,” rather than political prisoner. What’s the distinction for you?

A political prisoner is active politically and has become a prisoner for that activity.

But there are other people who are innocent casualties of these vast clashes of ideas. People who haven’t actually made a stand for the freedom of their own country. A large number of those people at the end of World War II ended up in labor camps. Not heavy-duty prisons—the heavy-duty prisons were for the political prisoners—but they nevertheless ended up in captivity. They were just casualties of politics. In the book I wanted to play with the word prisoners so “prisoners of politics.”

Do you assign different morality to them?

I wouldn’t use the word “morality,” but I would assign different justifications. For the second of those two things, I could see no justification whatsoever. For the first, even though I may not agree with the justification, I can see a justification. There is no reason for the second. About 200,000 Poles, the vast majority of which were not activists for or against anything, were displaced in their own country at the end of the war. They were basically taken away by the communists and put in labor camps or wherever. About 10 years later, after Stalin had died, they were allowed to go home again with no explanation.

Another thing that Feliks’ mother says is that Stalin was worse than Hitler. Do you also believe that?

I think you can make that case, but it’s not a case that I would make. This part was edited out, but the conclusion that Feliks reached in the last chapter is probably closest to my feeling. He says that as human beings, they were probably on par with one another, but you couldn’t judge them only as human beings because they were also representatives of an ideology. Feliks makes the point that fascism is an evil ideology full stop, whereas communism can at least be portrayed as a noble ideology. The ideology itself is set out to help the human race—which fascism never set out to do. It may have been completely impractical, and it certainly failed, but as an ideology it isn’t evil.

In an interview with New Zealand’s The Dominion Post, you said that you are more attracted to doubt than ideology. What is the value of doubt?

The value in doubt is that you’re unlikely to ever impose your convictions on other people with force because you’re not completely sure that you’re right. It’s a cliché, but it’s true: the more you know, the more you discover that you don’t know.

As life goes on, I’ve become less certain about those things. I still believe what I believe, but I’m not going to assert that what I believe is some universal truth or set of truths, which therefore, everybody else should believe. I think that if the whole world managed to have that doubting attitude, it’d be less inclined to impose itself on other people.

You were active in politics for years, worked on several campaigns, and even made a bid for public office yourself. Have you’ve become disillusioned by politics?

No, I’m not disillusioned. But I’m also more fluid in political attitudes than I was when I was younger. I really don’t think one ought to be disillusioned by politics ever, even though it frequently causes one to be disillusioned. But if you do think that having a democratic system, for all its imperfections, is better than having any other system, then somebody has got to make that system work; and even if they fail, then somebody else has got to try and do better next time. You’ve got to keep believing that things can get better.

Just as there’s no such thing as a perfect human being, there’s no such thing as a perfect government or a perfect political party. They’re all collections of human beings and have all the faults that we’ve all got as individuals—and the virtues as well. But they’re never going to be perfect.

I know I’m generalizing but one thing that is lovely about America is that you are enormous optimists. You find it a lot easier than us world-weary, cynical Europeans to place all of your trust in a person as you did with Barack Obama. Now, two years later, there is disillusionment. I think that is unfair on the man because expectations pinned on him were the most extraordinarily difficult circumstances—both at home and abroad—that no human being could possibly deliver on completely.

You set the book in 1991 at the end of the Cold War in Europe. Why is this time period still relevant?

I love to try and make sense of the times that I have lived through. The setting isn’t contemporary, but it isn’t the ancient past either. It’s kind of hovering somewhere in between. But for a great many people who lived through the period of communist domination of Eastern Europe, it is still a huge subject. And also for those who didn’t, it might actually be interesting to know a little bit about it.

When we learn history in school, history stops arbitrarily roughly 50 years before we’re being taught. History curriculums are set by people who are at least one, if not two, generations older than the people being taught. Because they’ve lived though them, those 50 years aren’t history to them, those years are actually current affairs.

This black hole of history poses a huge danger because our leaders need to be aware of history and most of the relevant lessons are the lessons of recent history. You’ve permanently got generations of world leaders who are pretty hazy about the very history they should be drawing lessons from.

Read Elizabeth’s bio.

One Comment on "Jim Powell: “The Eggs Broken Were Millions of Human Beings”"

Having read this I thought it was really enlightening.

I appreciate you taking the time and effort to put this information together.

I once again find myself spending a significant amount of time both reading and commenting.

But so what, it was still worth it!