Also Sprach the Puppet

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / January 29, 2014 / No comments

Song Binbin, a former Red Guard, officially apologizes…

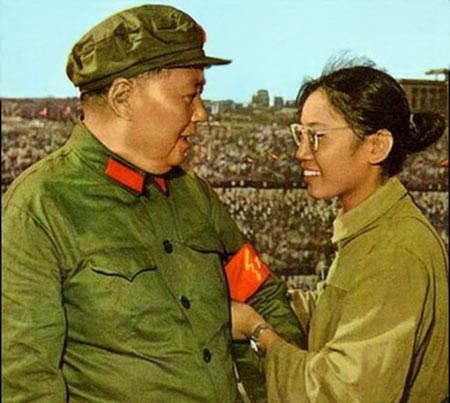

Song Binbin pins a Red Guard armband on Mao Zedong, Aug. 18, 1966. Photo via WantChinaTimes.

When the 17 year-old student Song Binbin pinned a red band reading “Red Guard” on Mao Zedong’s arm on August 18, 1966, she poured more fuel directly onto the already inflamed Cultural Revolution. Through this act, Song became the symbol of the movement’s young, rebellious revolutionary generation, which, according to the party jargon, “touched the soul of the people” and determined their fate over the following decade.

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison till 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

Forty eight years later, now living in the United States as a scholar, Song Binbin finally showed regret for the actions of her youth and said “sorry” to the victims and their families at her former school, Beijing Normal University-affiliated middle school. Mrs. Bian Zhongyun, the school’s late principal, was beaten to death by her students on August 5, 1966—just two weeks before Mao met with Red Guard leader Song Binbin. Bian’s death was the first well-known case of an educator being killed by their own students. In the months and years following, thousands of teachers fell victim to the students’ violence.

The general opinion is that Song was responsible for the death of her school’s headmaster. This year, on January 12, Song and some of her former classmates visited the school and bowed to the statue of the late Principal Bian. Song then gave a short speech and said, with tears in her eyes, “I am responsible for the tragic death of Principle Bian…I was worried that others would accuse me being ‘opposed to fighting against the black-gang.’ I did not and had no possibility to prevent the armed fighting against principle Bian and other administrators.”

But are these words from her heart, or are they just a trick to wash herself clean? Did Song intentionally word her apology to say that she wasn’t directly involved in the beating? If we allow more guesses, we could ask if this was a fabricated act, backed by the party. Her apology distracted national attention, while her initial actions expanded Mao’s catastrophic political movement into a widespread youth outbreak.

Also involved in the Cultural Revolution, but not as a leader or hero, was Wang Rongfen, a female college student who was sentenced to death and imprisoned for 11years. Lately, Wang has criticized Song, and doubted the sincerity of her apology; a simple word like “sorry” cannot comfort the victims’ loved ones. Wang has also said that the Cultural Revolution is a crime against humanity, comparable with the Nazi holocaust.

Indeed, Beijing Normal University-affiliated middle school was, and still is, an elite school. At that time, the majority of the students were the children of high cadres. Song’s father, Song Renqiong, was one of the most famous and powerful generals of the Republic. This red princess then became a star through the photo that was taken of her and Chairman Mao. When Mao heard Song’s name, Binbin, which means “civilized and polite,” Mao said: “It should be ‘want violence.’” Henceforth, the young girl was known as “Song wants violence” and led the Cultural Revolution’s crusade through the country in the following years. Mrs. Song left China in the 80s and became a scientist in the United States. She’s never commented on her own Red Guard past. Yet, in 2007, she went back to her alma mater and was honored as one of the school’s 90 most outstanding alumnae. She got the award not because of her achievement in science or some other contribution, but because of the moment she had with Chairman Mao. Obviously, she wasn’t ashamed or uneasy about accepting the award. Now, seven years later, she makes a theatric display as a sorrowful aged woman who regrets the foolish and irresponsible behavior of her youth.

Confession and atonement belong to the Christian ethic. They are rather unknown concepts on the Chinese mainland, where citizens have lived under decades of Marxist materialism. Mao criticized religion as the opium of the masses. In the Asian mentality, you show your guilty feelings or regret through concrete reconciliation, but do not speak of it in words or writing. The perpetrator of the Cultural Revolution is Mao Zedong, his entourage and the CCP, the Red Guards, were his puppets and instruments from the beginning. Later, they got out of control and became a killing machine.

Today the Red Guards’ generation have reached middle- or old age and, looking back on those chaotic years, they feel cheated and betrayed. They call themselves the lost, disillusioned generation. During the so-called “ten chaotic years,” schools were shut down and young people lost any chance of education: There were no books, no teachers, and no newspapers besides the Party organ. The whole country was a cultural desert and the ragged economy was on the edge of disaster. The “down to the countryside movement” drove millions of youth to remote regions to become peasants. Harsh circumstances stole their youth, dreams, hopes, and health. A part of them is lost forever, and a part of them struggled and survived. Song Binbin belongs to the survivors. She has lived in the free world for about 40 years, and now, at 65, she’s coming to terms with the past. Didn’t she come to the idea earlier? Was the idea to apologize to the dead principal and persecuted teachers from her own mind and will? Why did she do this so officially at the school and not go directly to Bian’s husband and beg for his forgiveness? Her speech sounds so pointless and ambiguous; it didn’t reach people’s hearts. The tears are from Song the agitator, not from the victims or their families.

People can forgive the political mistakes of a 17 year old girl, but they don’t want to see an inferior performance from a 65 year-old woman.