Sapphire on Precious’ Emancipation

by Elizabeth Hoover / October 4, 2010 / 1 Comment

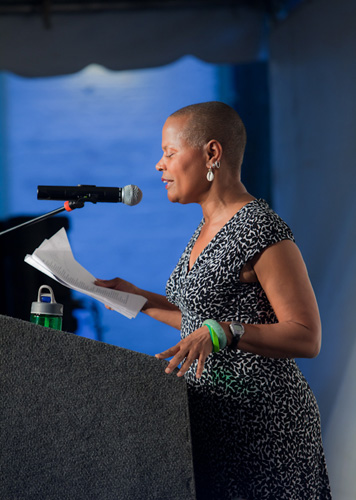

Voices of Cave Canem

It should come as no surprise to readers of Push, Sapphire’s bleak and unsettling novel about a Harlem teenager impregnated by her father and abused by her mother, that the author compares her dark vision to that of Edgar Allen Poe.

Unlike Poe, Sapphire has been lambasted by critics, who accuse her of portraying the black community too negatively. In this interview, Sapphire defends her choice as a matter of artistic freedom and explains how the story of Push, despite its rawness, is actually about liberation and the power of language.

Sapphire, a native of California, began writing and performing her poetry during the height of the slam movement in New York City. Her first commercially published book, American Dreams, a collection of poetry and prose, was lauded as “one of the strongest debut collections of the ’90s,” by Publishers Weekly. Her novel Push was adapted into the Oscar-nominated film Precious by Lee Daniels. She is also the author of Black Wings & Blind Angels: Poems.

In June, Cave Canem, an organization for African-American poets, held its annual retreat at the University of Pittsburgh’s Greensburg campus and joined City of Asylum/Pittsburgh for a free reading on Pittsburgh’s North Side. This is the second interview in a series of interviews with the poets who participated in that event.

Read the first interview, with Carl Philips.

Push follows the life of Precious, a black teenager living in Harlem. You once said of Precious that people who love to hate people like her ended up loving her. Why do people initially hate Precious?

The book Push was published in 1996, at a time when Newt Gingrich was standing up in Congress saying that an unmarried 17-year-old with a baby is not a family. It was also a time when African-American women and poor women on welfare were being vilified as the cause of the economic downturn of the country as if the money that was being doled out for welfare was enough to sink us.

Precious is all that is negative in White America’s eyes. She is dark; she is obese; she is poverty-stricken; and she is ignorant. She is seen as a something to be eliminated, like the so-called welfare queens who were considered to be a real problem at that time.

It seems like in a lot of these debates the focus is on the women who get pregnant, not on the men who—

Impregnate. There have not been a lot of studies on poor women, but the few studies that have been done show that many of these teenage women are victims of family sexual violence. From early childhood on, they are literally preyed on by older men. We aren’t talking about two young people falling in love who get together and have a baby. These are older men who serially attack young women. But in no way is that ever really looked at in this country. I mean, it wasn’t until Eliot Spitzer that we’ve looked at “The Man.” Even with Bill Clinton, the coverage was more about Monica Lewinski and how she was morally depraved.

For me one of the hardest parts about Push was not the depiction of Precious, but of Mary, Precious’ mother. She really challenges the stereotype of the mother as instinctually caring for her child.

The economics of the patriarchal culture in which we live get in the way of Precious’ mother’s instinct to the point where it warps it like a piece of steel hit by lighting. In her mind, Mary has to choose between her man and her child. Of course, the culture tells her: you are nothing without a man. Then there’s an economic incentive in terms of her using Precious and her children as a means of support.

While I don’t know if it’s her instinct per se, certainly all of those economic forces have warped her maternal duty to prepare her child for adulthood and let her go. But even as she abuses Precious, she’s trying to hold on to her because Precious is a source of income. So all of these things—Mary’s poverty, Mary’s submission to her patriarchal paradigm—cause her to turn against her own child, in addition to her just being a weak and warped person. By nature, she is an evil person who hasn’t done any, as we would say, “work on herself.” She’s a very lost and confused woman.

A lot of the criticism of that book came from writers of color saying you depicted the black community negatively. How do you respond to that?

That’s something any serious artist has to resist. Imagine if they had come to Kafka after The Metamorphosis and said: “Look how you depicted the Jewish family; you depicted Gregor Samsa as bug and his family as killing him. Is the family so filled with greed that they kill him once he doesn’t go to work any more?”

Are artists going to bend to the dictate of a community and paint a false picture? Or, even if there is a lot of positivity within that community, don’t I get to choose my job? Suppose I wanted to spend my whole life, like Edgar Allen Poe, looking at the dark side of life? I have a right to do that. Artists can pick their subject.

I understand that people sometimes need more positive images, often at the expense of the truth, but it’s not my job to supply that. I haven’t chosen that. There are a lot of people who are doing uplifting things and I support them. Instead of complaining about the art you don’t like, get behind the art you do like.

Precious is often described as illiterate, but you chose her to be the written voice of the book. You explicitly show she is engaged in the act of writing, not speaking, the narration.

Exactly. That harkens back to the earliest traditions of African-American writing, where the acquisition of literacy was acquisition of freedom. In the early slave narratives, you see links between literacy and freedom. If you could write letters that allowed you free movement, you could escape. For example, Frederick Douglass learned to read on the sly and that enabled him to write the note that said, “My slave is going to the market, let him go.”

In the beginning Precious is basically enslaved by her mother and enslaved by her ignorance. Through the acquisition of literacy, she finds her way out. Sure, it’s a fantastical, gothic type of modern story, but it’s also a realistic story. Instead of having her win a million dollars on a game show or having someone fall in love with her and transform her life, she transforms her own life through the acts of reading and writing.

It ends up being a much more positive message than say a feel-good comedy about black people winning the lottery.

It’s do-able. Every young man and woman can learn to read and write, but not many people are going to win a million dollars. Vast numbers of young women—especially women of color—will have trouble finding husbands. So reading and writing is a very realistic and positive goal. It puts you in control of your own life, as opposed to looking outside of yourself for someone to heal you, to transform you, to accept you, or to love you.

At Sampsonia Way, we focus mainly on issues of freedom of expression internationally. What obstacles do you see for freedom of expression here in America?

I read in The New York Times that for the first time the majority—that’s sad!—of young people in California who were applying to junior colleges didn’t get in. The junior colleges are flooded. Making education out of people’s reach is a form of censorship. We’ve gone further and further away from the public school system as well. The public school system is meant to imbue us with education and literacy and language. We don’t have that and that’s a form of censorship. Most people don’t even know it.

Read Elizabeth’s bio.

One Comment on "Sapphire on Precious’ Emancipation"

Trackbacks for this post