Why Not Choose Names from Various Cultures?

by Tarık Günersel / June 7, 2013 / 1 Comment

Choosing many names as a symbolic step toward world society.

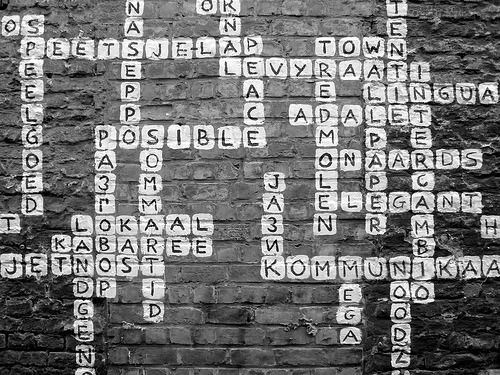

One can choose a name or names from an area of conflict as a symbolic step toward a world society that transcends national limitations. Photo: Amaury Henderick via Flickr.

My new name is Arwin Baran Lao Luys Marco Thales Zinderud Tarık Günersel. But you can just call me TG.

I was born in the year XIV5953. I consider myself not 60 years old, but 14,000,000,060, as a sign of respect to the rich history of the universe that led to my genes. Though I was “naturally made” by a Turkish couple in Istanbul, my name,Tarık, (“i” without a dot) is Arabic, and means “morning star.” There is a similar word in Arabic, “tarik” (this “i” is with a dot), which means “path.”

- Life is words in action, literature is action in words.

Humans are about to destroy their spaceship Earth. Some of them are aware of this and they try to change the course of events. Will they succeed? Will more humans be alarmed and do something?

Literature is vital and translators are messengers of world peace.

Though I shall focus on the literary scene in Turkey and its problems regarding freedom of expression, I shall not omit the other parts of our planet. Today local is global and vice versa.

- Tarık Günersel is a poet, playwright, aphorist, librettist and short story writer. He is the president of PEN Turkey and an ex-member of the PEN International Board. He studied English Literature at Istanbul University. A self-exile after the military coup in 1980, he spent four years in Saudi Arabia with his wife Füsun and their daughter Barış, teaching English. A dramaturg at Istanbul City Theater since 1991, he has acted on stage and screen and directed some of his plays. He proposed World Poetry Day in 1997 which was accepted by PEN International and declared by UNESCO as the 21st of March. His translations into Turkish include works by Samuel Beckett, Vaclav Havel and Arthur Miller. His works include The Nightmare of a Labyrinth (mosaic of poems and stories), and How’s your slavery goin’? His Oluşmak (To Become), a “life guide for myself,” includes ideas from world wisdom of the past four millennia.

There are eight vowels in Turkish, which, in our Latin-based alphabet (thanks to Atatürk, who wisely abandoned the Arabic script in 1928) are a, e, ı, i, o, ö, u, ü. The second syllable of my name is with ı, not i, and it is pronounced like the ‘e’ in the second syllable of the word “paper.” But I accept my name as expressed within the limits of the English alphabet as well.

In 1934 a new law made it obligatory for each Turkish citizen to have a surname. My grandfather, Necmeddin, (Star of Religion), a secularist Muslim thinker who was 35 at the time, chose the surname Güner, which means “the time of sunrise.” The officer in charge commented to be helpful: “But there are already a lot of families by that name.” When I was a child, my grandpa told me: “So I simply added the word sel. It means ‘flood’ in Turkish. But it is also a suffix that means ‘related to.’”

A decade ago my friend Pali Canon (the name he chose for himself) decided to call me “Zinderud.”

“It means ‘Living River,’” he said.

Thanks to the International Writing Program, led by poet Christopher Merrill at the University of Iowa, nineteen poets and scholars recently gathered in Konya, the city where Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi wrote his major works in the 13th Century. My fellow Sampsonia Way columnist Bina Shah was also among us. When I mentioned my desire to select new names from various cultures, young Somaya from Afghanistan joyfully shouted from her table: “Arwin! I’ll call you Arwin! It’s a Persian name. It means ‘experimental.’”

Then I asked Nigol, our filmmaker, to choose an Armenian name for me. “How do you say ‘Good morning’ in Armenian?” I asked him.

He said, “Pari luys. Luys means light,” and called it an appropriate name. Golan, who had come from Syria, liked the name Baran, which means “rain” in Kurdish.

I chose ‘Lao’ after the Chinese thinker Laozi, ‘Thales’ after the Greek philosopher (or ‘philactosopher’) who is considered to be the initiator of scientific thinking and naturalism, and the first name of Marco Polo. To make it easy to remember, I put all my new names in alphabetical order: Arwin Baran Lao Luys Marco Thales Zinderud Tarık Günersel.

So now my names are from Persian, Kurdish, Chinese, Armenian, Italian, Greek, Urdu, Arabic, and Turkish cultures.

What good is this? In addition to the pleasant adventure of selection, I can feel and think in a wider spectrum. That is why I have chosen some of my names from areas of conflict. It is a symbolic step towards a world society that transcends national limitations –naturally related to ECP –Earth Civilization Project.

One Comment on "Why Not Choose Names from Various Cultures?"

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this Tarik (I couldn’t find the dot-less i, please forgive me). Man has divided the world, and throughout all of our differences we are fundamentally the same, so, why not take steps, symbolic or physical towards “transcend[ing] national limitations.” Starting with names is great. In Igbo culture names are extremely important. Child-naming is always marked by a ceremony and are complete expression, full of meaning and reflection of certain experiences and circumstances that occurred during childbirth, the child’s journey to earth, and even social expectations for that child and their family. Oh how much we can learn just from names.