In the Mirror, Left and Right Meet

by Israel Centeno and translated by Kelly V. Harrison / November 6, 2012 / No comments

The hypocrisy of the modernized Latin American State.

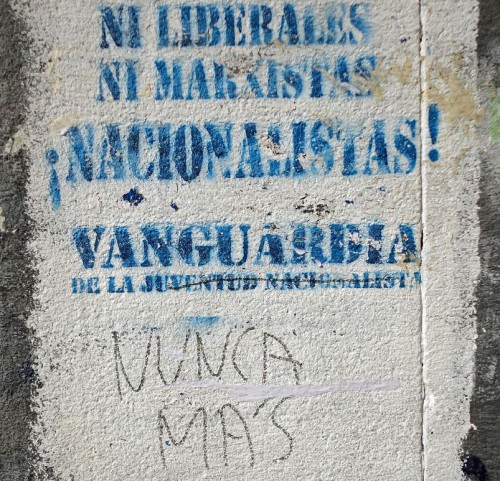

Graffiti from Buenos Aires. Photo: Carsten ten Brink. Translation: 'Neither Liberals Nor Marxists; Nationalists!; Nationalist Youth Vanguard; Never Again'

Generally in Latin America, when we hope for a change in government, our attention is focused on replacing the élite, the parties, and the incumbent leader. Very rarely do we discuss the need to modernize the State. Perhaps the last big debate, nearly fifty years ago, was between the liberal and republican presidential models versus the ideas framed by national liberation and socialism. Those who embodied the latter stance took on the neo-colonial character of our Latin American nations and, inspired by the reality in the Soviet Union and China, concluded that socialism was the only way to achieve modernity and development. These debates were led, in most instances, by a middle class unhappy with statist populism.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

However, even before the republics were born the voice and the will of the people was usurped and abused. The flags of independence, the subsequent uprisings, the peasant revolts, and the restorations were initiated, or capitalized on, by messianism. They were initiated in the name of the people, minorities, and the ideals and values most sacred to the homeland. And it was those people, who were left in the margins or found in the crossfire, from whom a quota of blood was demanded (without them having been asked). All of this was done in order to establish control of a corrupt centralist government that reallocated privileges and was backed by soldiers’ bayonets in an implicit way—if not commanded directly by one of the officers.

Nowadays, we could say that most Latin American countries have governments with large, complex state structures. Many of the presidents who align themselves with the political left embody the traditions of the redeemer, the populist vindicator, and the hand that delivers social justice. However in the shadow of these great, powerful states, a growing class of privileged people remains. It is a class of people that cannot even be called the bourgeoisie, as it is not productive. It is a voracious and criminal class, tied to a range of shady businesses.

In Venezuela the scene is increasingly strained. Fueled by income from oil, the situation is getting worse. The far-from-presidential system of government, led by a caudillo with a parasitic and corrupted military and political ruling-class, releases foreign capital in the name of those who have been excluded.

Seeking discourse on modernization in Latin America could be a very difficult task, as there is not an attractive alternative, given that economic liberalism is back with an account balance in the red. But stereotypes seem to be mirroring one another, from one side of the hemisphere to the other. Only the symbols have changed. The caudillo-led Latin American left mimics the jingoistic, pre-modern right of the northern hemisphere: It is militaristic, it depreciates diversity, freedom of expression, and thought, it is not at all secular, and it is devoted to corporations. The only difference here is that, in the south, the surrender to transnational corporations is disguised by the clichés of nationalist hypocrisy.