Liu Xia and Her Dolls

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / September 26, 2012 / No comments

A loss and a win for an artist in isolation.

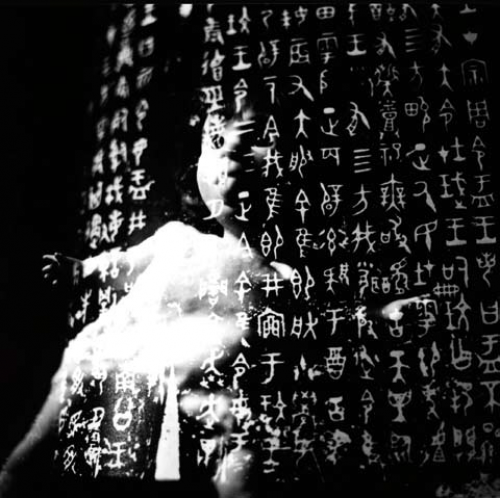

From The Silent Strength of Liu Xia. Photo: Liu Xia, courtesy of Guy Sorman.

One evening some of Liu Xia’s friends snuck into her yard and, seeing her silhouette in the window, took her picture from below. It’s only a shadow, but one can easily recognize her bald head and slim upper body. The image is a bit unreal, like a leaf trembling in the wind. How does this woman survive a Robinson Crusoe-style isolation, living without connection to the outside world among Beijing’s 20 million? She has neither phone nor Internet nor visitors nor family. Her only company are the security police. But she has not broken the law or committed any wrongdoings; the only reason for her confinement is that her husband is a political prisoner who has been granted the Nobel Peace Prize.

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison till 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it andso can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China

from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

Liu Xia is a poet and photographer. She married Liu Xiaobo when he was thrown in jail for the third time in 1996. Afterwards they were separated for three years while he served at the re-education camp until 1999. Currently, however, they endure a longer separation. Liu Xiaobo was an initiator and promoter of Charter 08, a document describing how China could change into a democratic society. As such he has been sentenced to 11 years imprisonment for “inciting subversion to state power.” He will not be released until 2020.

Liu Xia does not know that her photos have been exhibited in Berlin as a highlight of the Berlin Literature Festival (Sept 4-15). But Liu Xia’s pictures, with dolls as their central subjects, have attracted the interest and attention of the public.

In the photographs we see an allegorical rendition of the couple’s daily lives: Liu Xiaobo, fighting fiercely with his words against a repressive regime that stifles political and artistic freedom; the sensitive Liu Xia documenting the spiritual condition of an artist inside the big prison called China. The photos are set inside tall walls, behind sturdy iron bars, on gigantic cliff sides, amid ominous men in shadows, and in the middle of desolate wilderness. The subjects that populate them are not humans, but dolls, which are hidden nervously behind and among piles of books, perched alone on the edge of a steep cliff, locked inside a cage, or squelched by a merciless hand. With Liu Xia’s photographs these lifeless toys become alive, sharing their stories of dismay, pain, solitude, defiance, and resilience with the outside world.

Ironically, the photos, taken by Liu Xia years before, offer a prescient glimpse of her present life. The Chinese authorities have imprisoned her husband since December 2008 (the fifth time he has been held in custody) and his incarceration led to Liu Xia’s house arrest, possibly a more torturous form of punishment. At this very moment, Liu Xia is living under 24-hour surveillance, conducted by the public security police—a group of faceless men lurking around her apartment like shadows. While her husband might have the companionship of fellow inmates, Liu Xia is alone. Her contact with the outside world—with her friends or relatives or the media—is completely cut off.

For Liu Xia, police threats and imprisonment are nothing new. Over the years, as her husband went in and out of jail, Liu Xia defiantly faced the constant police harassment and loneliness. There is no doubt that these living circumstances cast a strong influence over her photographic works. There is a popular Chinese saying: “The loss for the state is a win for the poet.” The agony and sorrow the couple has endured have shaped their work, making them truly exceptional artists of our time.