Denialistan: Part Two

by Bina Shah / June 12, 2012 / No comments

Should Pakistani writers hide their country’s problems from the world?

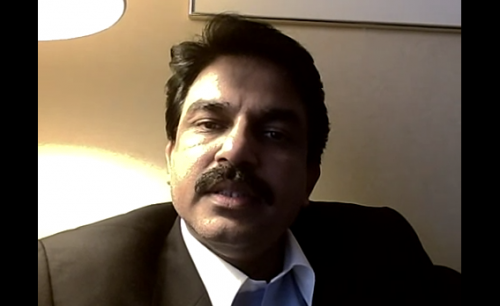

Shahbaz Bhatti, Minister for Minorities Affairs, was murdered for speaking out against blasphemy laws. Photo: Youtube user AlJazeeraEnglish

In the first installment of Denialistan Shah called some of a book club’s members Denialistanis after they criticized her book Slum Child for its depiction of the discrimination Christians face in Pakistan.

- Pakistan is a country of contradictions – full of promise for growth, modernity and progress, yet shrouded by political, social and cultural issues that undermine its quest for identity and integrity. My bi-monthly column “Pakistan Unveiled” presents stories that showcase the Pakistani struggle for freedom of expression, an end to censorship, and a more open and balanced society.

- Bina Shah is a Karachi-based journalist and fiction writer and has taught writing at the university level. She is the author of four novels and two collections of short stories. She is a columnist for two major English-language newspapers in Pakistan, The Dawn and The Express Tribune, and she has contributed to international newspapers including The Independent, The Guardian, and The International Herald Tribune. She is an alumnus of the International Writers Workshop (IWP 2011).

Some of the other members of the book club said that as a writer, I had the right to write whatever I wanted, and that the “truth” is a subjective concept anyway. Besides, what was wrong with pointing out the ills of our society? Isn’t that what a writer is supposed to do? “But it will give a negative image of Pakistan to the world,” came the response. Yet Slum Child had to be written, I said. It’s my job as a writer to speak honestly about what I see.

Then a woman further down the table spoke out, saying she was a Christian and that everything I was talking about, she had experienced. She started talking about how many times she’d lost out on a job opportunity or been humiliated for her religious beliefs. She said that she had been called “shameless” and other epithets, and that she was told Christians had corrupted the “pure” religion, a belief common to many Muslims, and one which I had written about in Slum Child.

She kept seeking out my eyes, and I felt the strongest bond of connection that I can remember feeling with another human being, let alone a complete stranger. It was as if she was telling me that she knew I understood. And I was telling her that I did. In writing the book, and speaking the way I had that evening, I had validated her experience of being discriminated against. I had shown her that her struggle had not gone unnoticed. That, to me, was “the truth.” Knowing that I had reached one person who needed to hear this message felt better than if I’d sold a million copies and appeared on Oprah’s Book Club.

For many days after the event my mind kept going back to that Christian woman in the book club, who, when the evening ended and I was preparing to leave, took me aside and asked me how I had the courage to write and speak about such controversial subjects. She thanked me for coming that evening, and said that I had given her the courage to talk about her experiences. Previously she had bottled them up inside her, unable to write them down. “Every time I tried, my pen would just stop after a few paragraphs,” she said.

I told her I was stupid, not brave. She was the brave one for living that life, not me just for writing about it.