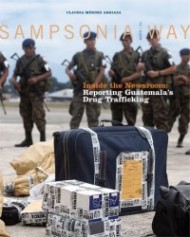

Inside the Newsroom: Reporting Guatemala’s Drug Trafficking

by Claudia Méndez Arriaza / September 28, 2011 / No comments

Drug trafficking, and the violence it engenders, is Guatemala’s latest threat to freedom of speech. In her exclusive letter for Sampsonia Way, elPeriódico‘s Claudia Méndez Arriaza uses her inside-the-newsroom perspective to compare the risk of being a journalist today with the risks of reporting during Guatemala’s bloody civil war (1960-1996). She also discusses the necessary precautions for staying alive while reporting on drug-trafficking in one of the most violent cities in Latin America.

The US State Department estimates that at least 75 percent of the drugs distributed in US territory are trafficked through Guatemala. The confiscation of drugs and money (as in the above photo) are events covered by the local media.

Long before I became a court reporter for elPeriódico de Guatemala, the career of many of my country’s journalists had been terminated. Some abandoned the newsrooms for less complicated jobs; others vanished from their desks and typewriters—only to show up in the morgues as further victims of political violence, or as one more desaparecido on the long list of casualties in Guatemala’s civil war.

Just type these five words into Google: “periodistas asesinados conflicto armado Guatemala” and the search engine will retrieve hundreds of thousands of pages. It is the same with any search, you might say. But there is a difference in this case: This is not just a search for the right restaurant or hotel; these are pages about reporters assassinated during the war; this is the history of journalism in my country.

And sometimes an internet search will show you what you don’t want to know. For example, in April 2000, a Spanish journalist was about to travel to Guatemala to work as a trainee for Prensa Libre, one of the country’s largest newspapers. When she tried to show her family the paper’s website, the computer screen showed the latest breaking news: A photographer had just been shot down while covering a violent demonstration. The journalist’s mother begged her not to travel to Guatemala, but she did, and that is how we, her Guatemalan peers, heard about that story. We could only laugh.

While doing my own Google searches about assassinated Guatemalan journalists, I found a website that compiles facts and figures I’d never seen all in one place. Reading this page, I learned that during the 36-year-long Guatemalan civil war 342 journalists were assassinated and 126 were illegally arrested or disappeared. That makes an average of at least one attack on the press per month, consistently, between the years of 1960 and 1996.

The statistics come from the Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo (GAM), a group of the victims’ relatives that emerged during the war. The website also says that there was no investigation into any of these deaths, nor has there ever been a trial for the case of a journalist who disappeared during that time.

Nonetheless, the same website explains that there is no longer a “política de estado,” or “state policy,” in Guatemala on violations of freedom of expression. Peace Accords were signed in 1996 at the end of the civil war, and after that it is fair to say Guatemalan journalism became a very different story. The dark days faded into the light of a new era when a generation of journalists emerged from universities and filled the newsrooms with reporters in their twenties: Young men and women who faced the challenge of starting their careers while writing a new chapter in the history of their country.

Drug trade killings are characterized by the high number of bullets fired. Such killings often occur in daytime and in the crowded areas of Guatemala City.

Crimes That Never Happened…

Since the Peace Accords were signed, there have been threats. There have been illegal raids on the houses of several journalists. There have been threatening calls meant to frighten journalists into silence. There have been advertisers that vanished from our pages and, in an economy as small as Guatemala’s, sometimes one advertiser can speak for ten businesses.

Freedom of expression is still vulnerable from all perspectives, yet it is hard to compare the number of journalists who have been killed or threatened during the last 15 years with the number of deaths during the war.

Cerigua (Informative Report Center of Guatemala) is a news agency which describes itself as an alternative media in Guatemala. It also runs “Observatorio de los Periodistas” a project focused on freedom of expression for the press. Ileana Alamilla, the director of Cerigua, explained to me that since 2003 the observatory has worked to compile and make public every case of violated freedom of expression in Guatemala: A total of 394 from 2003 to 2010.

Cerigua clarifies that the figure includes verbal and physical aggression, attacks, threats, harassment, persecution, intimidation, defamation, reporters harmed by bullets, and even allegations from reporters of attempts to limit their access to information. The hard number comes later: Out of those 394 cases, the number of assassinated journalists is 20.

What has not changed in Guatemala since the war is the judicial system’s response. It is rare to hear that any of the crimes Cerigua documents make it to the courts for a trial. Impunity is severe here and sends a radical message: An unpunished crime is a crime that never happened.

So the weakness of the institutions and the fragility of the so-called Rule of Law undermine the peace process that was started in 1996. I’m not only speaking about freedom of expression here; I’m also talking about Guatemala’s effort to build a democracy.

Captured drug traffickers are afraid to testify against their organizations, and even when they do, reporters may be too intimidated to cover the story.

“The war is not with the press…Cut the bullshit before the war is against you.”

The civil war is over, but another armed conflict has arisen: The battle against the traffic of illegal drugs. Guatemala is located in such a strategic position that the US State Department estimates that at least 75 percent of the drugs distributed in their territory are trafficked through my country. We can argue about the figures, but the signs here are very clear.

I began to write this letter a few weeks after a horrible massacre of 27 peasants, which occurred in a farm in La Libertad, Petén, a northern department located 507 kilometers away from Guatemala City. Only days after that, a young district attorney was slaughtered in Cobán, Alta Verapaz, 219 kilometers to the north of the capital city.

All of these victims were beheaded.

ElPeriódico is based in Guatemala City. You must travel 4 hours to get to Cobán and 8 to get to La Libertad. But fear travelled faster after the killings and, like a dark and heavy blanket, it covered the newsrooms based in the city. I won’t ever forget the face of the youngest reporter in elPeriódico, who also happened to cover the police. I was his editor that day; he came to my desk and said, “I’m not going to sign those stories, please take out my byline.” His reasons were obvious: I saw miedo, the fear in his face, and he seemed so vulnerable. Shy and funny, young and skinny, with long hair that draped over his forehead. Still a college student, who’d been working at elPeriódico for less than 4 months, he had covered the events of one of the more violent cities in Latin America: A place with 17 to 20 crimes daily, in a city of 3 million inhabitants.

I thought it was normal for him to ask for his byline to be removed, being so young, but the next day when I read the daily papers I was shocked to see that no journalist in Guatemala had signed their stories—not even the follow-up stories related with the massacre were signed. One of the largest and most traditional papers here also decided not to include any of those events on the cover of their editions. Instead, the killing of the prosecutor was a secondary note on page 10.

Then my question was: In which country in the world is a prosecutor beheaded, his body left with a written threat at the entrance to the governor’s office in his town, and it becomes a secondary story on page 10 in the country’s oldest paper?

In Guatemala.

The prosecutor had been part of a team that seized an important shipment of cocaine. The beheaded farm peasants, according to the threat, were working on a farm owned by a key contact of a criminal organization.

During the raids that followed the killing of the prosecutor, authorities found huge signs printed on blankets. Besides the usual threats and some explanation for the killings, was a warning against the press: “La guerra no es con la prensa así que llevémosla tranquila. Bájenle a tanta mamada antes de que la guerra sea contra ustedes…“; “War is not with the press, so let’s take it calmly. Cut out the bullshit before the war is against you.…”

Were those the lines that frightened the young reporter? Were those the lines that drew fear on his face? Were those three lines enough to end our enlightened decade of freedom of expression?

“Watch out. Things Are Going to Get Worse.”

After a gunfight between rival drug organizations, the glass of a storefront over an ad is shattered.

Silvino Velásquez is a veteran reporter. He and I found ourselves in a meeting organized by former journalist Carlos Menocal, who is now the Interior Minister of Guatemala. How did that happen? How did a reporter became a Minister? That’s another story; but what happened during the meeting is another sign of just how vulnerable journalists in Guatemala still are.

I interviewed Silvino Velásquez to write this letter. I was trying to make him compare the behavior of the press during the war with our conduct during this new era of drug trafficking. “Éramos más valientes antes” he said, “We were braver before.” I asked him what he meant. After he thought it over, he explained that in the eighties, directors and editors would never have demoted an important story to page 10 as a secondary note.

I asked him what the consequences were for journalists back then and he mentioned that he lost 25 colleagues. As I heard him, I thought to myself, that would be like losing the newsroom of elPeriódico. I don’t want that. No story is worth a life. No story.

The purpose of the meeting with Carlos Menocal that Velásquez and I attended was for Menocal to explain some of the actions that he and his team were taking toward managing the violence in Guatemala. But, by the end of the session he addressed us all and said, “Watch out. Things are going to get worse, and our lives are in the middle.” No longer speaking to us as Interior Minister, Menocal was talking as a journalist. He made it clear when he said, “I know that not all of you have life insurance; it’s important that you claim it.”

The Unwritten Protocol for Covering Drug Trafficking

As a safety precaution, I monitor reporters when they are away from the office. In November a journalist from my team took a trip to find out why a man facing charges of transporting tons of cocaine to the United States had at least two hundred peasants demonstrating to support him and reject his imprisonment. When she visited his farms she found out that the demonstrators were his employees. During her trip we exchanged text messages constantly. Every time she moved from one place to another, I had to know about it.

Her work became a great piece that explained how the absence of “The Rule of Law,” or “The State” –abstract terms that mean so much—made it easy for some men, like the subject of her story, to gain a social base. If a man has given his community a school, an ambulance, a health center—if he gives money to the mothers of children dying from hunger—then it’s easy to become a popular man loved by the people, and it’s logical that people will get frustrated if the person who represents salvation for them is imprisoned.

It was not company protocol to text the journalist during her trip, it was a safety measure designed just for the occasion. Although, recently, while working with Greg Brosnan, a documentary filmmaker for London’s Channel 4, I learned that my older improvised methods could quickly become protocol.

Brosnan was working on a very sensible documentary about violence in Guatemala that explains how this tiny country found itself in the middle of a voracious drug war. I was hired as his contact person in Guatemala and soon the time came when he had to travel to the “red zone” of Petén and Cobán to interview people about the beheaded attorney and peasants.

I was going to stay in the capital city, but as a precaution I had to be in contact with him. There were two specific hours in which I definitely had to speak with him and then e-mail his headquarters to report that he was fine. Of course I called him more than I was supposed to. I thought that he was really at risk.

As with the young reporter in elPeriódico, I was either texting or calling just to be sure that everything was fine on the other side of the line. I fear the day that I call a journalist and get no answer, and I ask myself: Is this the way we should do journalism in Guatemala? I wonder sometimes if it is normal to think of danger when you think about your job.

I still sign my articles. I keep saying to myself and others that I will recognize whenever there is a threat ahead. But I am not the only one in danger; today many Guatemalans leave their homes in the morning, praying to return alive at night, and I wonder when is this culture of violence and fear going to end?

Claudia Méndez Arriaza is an editor and reporter for elPeriódico in Guatemala. She is also co-host of the television program “A Las 8:45.” In May she was named a 2012 John S. and James L. Knight Foundation Latin American Nieman Fellow, through which she will attend Harvard University for a year. While there Méndez Arriaza will study law and the politics of emerging democracies.