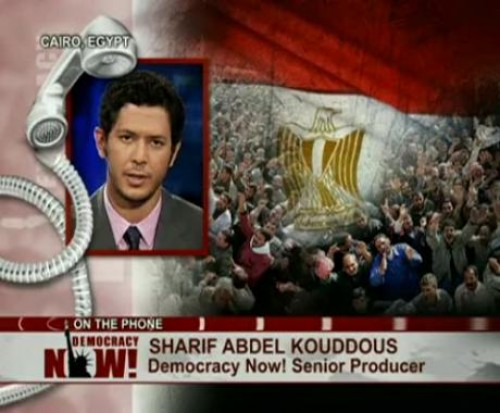

Reporting from Egypt: An Interview with Democracy Now’s Sharif Abdel Kouddous

by Caitlyn Christensen / December 19, 2011 / 2 Comments

Since the beginning of the Egyptian uprisings in January, journalist Sharif Abdel Kouddous has become an indispensable source for his Tweets and live reporting from Tahrir Square. From the ground in Cairo, he covers the revolution for the independent news outlet Democracy Now. Kouddous has been interviewed on The Rachel Maddow Show, and Hardball with Chris Matthews, and written for magazines such as The Nation. According to Democracy Now, his reports “capture the voices of the uprising” at its front lines.

Born in the United States and raised in Cairo, under Mubarak’s regime, Kouddous worked for two years at Bank of America as an investment banker before he became an independent journalist. “I hated the culture, I hated the work…So, after two years, I took some writing courses—I always loved to write—and I figured the only way I was going to get paid to write was in journalism,” Kouddous said in an interview with The Progressive. Now, he says he can’t imagine himself reporting from anywhere but Cairo.

In 2011, he moved to Egypt to cover the region in uprising. His work is supported in part by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

On December 12, Kouddous spoke with Sampsonia Way via Skype from Cairo. In the interview he talked about the nature of reporting in Tahrir Square, the role his nationality plays in covering the uprisings, and how reporting in Cairo has changed over the course of the uprisings.

How do you prepare yourself to cover a story in Tahrir Square, versus covering stories in the United States?

One of the philosophies that I learned from working at Democracy Now is to give people a chance to be heard. When I go to a protest in New York, or go to a protest in Tahrir, I always try to speak with a variety of people on the ground and get their opinions. In terms of approaching it, there’s not much difference.

There have been some very violent clashes between protesters and security forces here in Egypt, above and beyond what has happened in the United States. In situations like that, you want to report as much as you can from the front lines, and also balance that with the risks of doing it. In October there were 27 killed in the space of half an hour at a protest in front of the state TV and radio building here in downtown Cairo. So, in terms of levels of state violence, those situations are different than what I’ve covered in the United States.

I don’t know how to prepare for something like that; I think it’s a mix of experience and the willingness to go to the front lines and bear witness to what is happening, and be able to report it.

What was your experience witnessing the destruction and violence during the October 9 Coptic Christian protests? Why did you choose to write an eyewitness report rather than a news story?

The protest started peacefully, and I had no idea that it would be turned into a massacre. I was standing with a group of mostly Coptic Christians and some Muslims and other Egyptians who were there in solidarity. Many were holding candles, waiting for a big march to arrive, but when the march arrived the army began attacking the protesters. It is hard to think in such a chaotic situation, you are essentially running for your life at some points. So I tried to stay in the area as long as I could. Once I was out of danger, I went up a bridge to look from a different angle; I started speaking to people who were at the heart of what happened and saw what I didn’t see. I didn’t see the APCs [Armoured Personal Carriers] running people over, for example.

I went to the morgue the next day, saw some of the dead bodies, and spoke with the families of the victims. So, that report was less analytical; that’s why I called it an eyewitness report. It was just an account of what I saw and what I understood from others.

The massacre was a real human rights crime by the army–the ruling power in Egypt–but they immediately denied that they shot protesters and ran them over. That’s why it was very important to have documentation and eyewitness testimonies.

What was the role of Twitter for you during these uprisings?

I think the role of social media is important, but has been exaggerated by many in the Western media.

The first time I arrived in Egypt, on January 29, the Internet had been cut by the government and it didn’t work at all. Cell phones were also cut. What I managed to do was to text to the United States with my US cell phone. I gave a friend of mine, a prominent journalist named Jeremy Scahill, my twitter password; I texted him my tweets and he put them on my Twitter account. These were some of the only tweets coming out of Tahrir at the time. Because of that, my Twitter account grew by 18,000 in a couple of days. So I think in that sense, Twitter was an important way to send small news updates to the United States and elsewhere. However, since the internet was turned back on, Twitter is used very heavily, but just by a small section of the population.

Twitter is useful in, for example, the latest clashes that happened on November 19. Some people saw the attack and immediately began tweeting. In solidarity, people came down to Tahrir to protect them. So it is a very quick way of getting the word out. In situations like that I tend to Tweet a lot, but I wouldn’t substitute it for reporting.

Is your American citizenship an advantage or a disadvantage compared to other Egyptian journalists?

I am an Egyptian American but I report exclusively in English for US-based publications and news outlets. So, in that sense, I am somewhat more protected than local journalists who write for the Arabic press. The military, who has been in charge of the country since February 11, has interrogated, censored, and jailed journalists; it has stormed TV stations while they are on air and shut them down. The Supreme Council of Armed Forces has put a serious clampdown on the media and as a result there’s a self-censorship process: Recently, a new English-language weekly was internally censored.

As a journalist and as an Egyptian citizen, what are the rewards of covering the Egyptian uprisings? How do you perceive the historic nature of the current events in the land where you were born and your parents grew up?

As a journalist this is an epic historical moment and a turning point in Egypt’s history, so it’s difficult to find or imagine a more exciting place to be. The very foundations of the country are being uprooted and rebuilt. There is a counter-revolution that is happening, and there are forces seeking to repress change. But the fundamental change here is that the fear barrier has been broken and I’m hopeful because I think people won’t stand for it anymore. I think the struggle will continue to go on. So being here, as a journalist, has been an amazing growth experience. I can’t imagine being anywhere else at this time.

As an Egyptian, I grew up here and for most of my life the only Egypt I knew was the one under Mubarak. To witness such an epic revolution that involves dignity and social justice has been extraordinary.

As an Egyptian are you able to detach yourself emotionally from the events?

There is this false sense of objectivity that is promulgated in the United States. I think a lot of times that objectivity gets translated into stenography. What I mean is that you will find a lot of corporate media basically not being real journalists. They think that the range of the political spectrum is Democrats and Republicans, so they will say, “This side says this and this side says this,” and that will be the extent of their reporting.

What role has Western media played in covering the uprisings?

At first they said, ‘well the Mubarak regime says this and the protesters say this,’ equating the two sides. The truth of the matter is that this was a popular uprising that was being repressed by an authoritarian, US-backed regime. Calling things as they are is the essence of good journalism, even though that brings in emotion. This fake objectivity can destroy what reality is, and what is actually happening.

These mainstream journalists actually changed their tone when they came under attack by the Mubarak regime in the Battle of Camel, on February 2. Anderson Cooper, Christian Amanpour, and many journalists were attacked. The media could no longer deny what was happening through this fake objectivity of reporting each side.

It seems that when events are occurring far away from us, tragedy becomes minimized. Is this something the Western media perpetuates?

It might be. I think if you just give voice to people who are at the target end of these policies, then the tragedy presents itself. If you go to the morgue the next day after 27 people are dead, killed by the army, if you speak to their loved ones and hear what they are saying, there is no question that what happened was a tragedy. That is hopefully conveyed to people. Any journalist should do that.

Protesters recently attacked a French journalist, Caroline Sinz, and the authorities attacked Mona Eltahawy. Is there an advantage to being a male reporter while covering these protests?

There is a problem with sexual harassment everywhere in the world and it is pronounced in Egypt. Many female journalists, friends of mine, have told me that sometimes it’s difficult for them to report situations. However, they have been mostly attacked by protesters, not by security forces. When, like Mona Eltahawy, they are attacked by the security forces, I think the attacks are directed more towards western journalists than female journalists. Men have been attacked as well. There has been a rise of xenophobia that has been furthered by the state media. So it is easier to be an Egyptian than a Westerner reporting here.

Is it easier to be a man reporting in Egypt? Probably, yes; I don’t get harassed.

How does reporting in Cairo now compare to reporting at the beginning of the Revolution?

The risks have changed.

In January and February, in the first 18 days of the uprising, if you survived the Battle of The Camel you were safe once you were in Tahrir Square; the risks of being in the square were negligible. But it was risky being outside because the regime’s attacks on the media were furious. At the beginning things were a little more black and white.

Now it is more unpredictable. You don’t know when a protest can turn violent and the police or the army can attack it very brutally. You don’t know when an attack can happen or where it will happen. You don’t know when a reporter may be summoned to the military prosecutor to be interrogated. Things are a little more opaque, confusing, and tumultuous. So in that sense, it is a little more difficult to be a reporter right now.

Do you think the situation for journalists in Egypt will improve or get worse after the elections?

I think there is a big problem with the legitimacy of the elections to begin with; I wonder whether this parliament coming in will have any authority to challenge the military council. Right now the parliament does not have the authority to choose the prime minister, or the other ministers. It does not have the authority to sign treaties, or any real powers. Whether the election will change things, I don’t know. Whether the revolution will improve things for the media is the more important question, and I’m hopeful that it will.

Mubarak employed a variety of different techniques to clamp down on the media. The Supreme Council has not only continued those techniques, but in some cases, has furthered and expanded them. Right now the situation is difficult for many local journalists, but they continue to report things that are critical of the Supreme Council, and I think in the long run, things will improve for them.

What journalistic Egyptian blogs in English do you recommend?

The Arabist.net. There’s also Manalaa.net, which is mostly in Arabic, but there are some posts in English. Allaa Abdel Fattah keeps it with his wife, and he is a popular blogger who has written a couple articles out of prison. They just submitted an appeal two days ago and it was denied. His wife gave birth while he was behind bars.

Given the nature of your work, what do you do to unwind?

There’s plenty of things to do here. I hang out with friends, have a beer and shisha water pipe. (Laughs) I guess just what anyone does.

Kouddous’ latest report on Egypt. Democracy Now, December 19.

2 Comments on "Reporting from Egypt: An Interview with Democracy Now’s Sharif Abdel Kouddous"

Trackbacks for this post